Orientalism and Puccini’s Turandot

The core repertoire of today’s opera companies is largely based on works created at the turn of the 19th century. The period’s characteristic longing for faraway countries is crystallised in the concept of Orientalism.

What is Orientalism and how is it manifest in the arts?

The term Orientalism refers to a Europe-centric attitude to the cultures of the Middle East, Asia and North Africa. These cultures are considered inferior, static and undeveloped compared to European culture, which in turn is seen as “developed, rational and superior.”

The concept of Orientalism was introduced to western studies of art history by Edward W. Said, the author of the book Orientalism (1978). The Orientalist art of the 19th century cemented colonialists’ imperial power by separating the Orient (the east) from the Occident (the west) and presenting the former as inferior to the latter. Orientalist art from paintings to opera was mostly created by male practitioners and reflected the prejudices, stereotypes and fantasies characteristic of the time.

The fascination with Middle East and Asia manifested itself in either admiration or terror and involved regarding other cultures as a source of gratification for Europeans.

Orientalism, however, already existed way before the 19th century. Initially Turkish styles were in fashion, followed by everything Chinese, Indian, and Japanese. After the major European powers had their decisive victory over the Turkish Ottoman Empire in the 1680s, their neighbours to the east were no longer seen as enemies but as potential resources, in both a material and cultural sense. The rise of orientalism took place in tandem with the European conquest of the rest of the world. The fascination with Middle East and Asia manifested itself in either admiration or terror and involved regarding other cultures as a source of gratification for Europeans.

The period from the 1870s to the First World War was the heyday of imperialist attitudes, as European colonial powers took control of the majority of the world. As colonial exploitation accelerated further, Orientalism became a veritable mania fuelled by objects imported from the colonies. With the rise of consumerist culture, oriental objects became fashionable merchandise. Orientalist topics were firm favourites in the arts, which audiences marvelled at in World Expos. The Orientalising gaze turned people from distant countries into exotic Others. This was especially true for women from the odalisques of Middle Eastern harems to Indian priestesses and Japanese geishas. They were seen as exotic, passive objects of western men’s sexual desire. What’s more, the idolisation of foreign nations served as an antithesis to the perceived corruption of the industrial world.

This longing for the remote and the unknown is crystallised in many operas from the turn of the 19th century. Orientalist operas revolving around the Oriental Other helped feed European audiences’ fantasies about the exotic east. Examples of such operas include Pearl Fishers, which the French composer Georges Bizet set in Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka), his countryman Leo Delibes’s Lakmé set in India, as well as Italian Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot inspired by Chinese culture and Madama Butterfly set in Japan.

Chinese culture through an Italian composer’s eyes

Born in 1858, Giacomo Puccini composed a total of 12 operas in his lifetime. Only three of those are set in his home country, Italy. Orientalist attitudes are most prevalent in the aforementioned Turandot and Madama Butterfly.

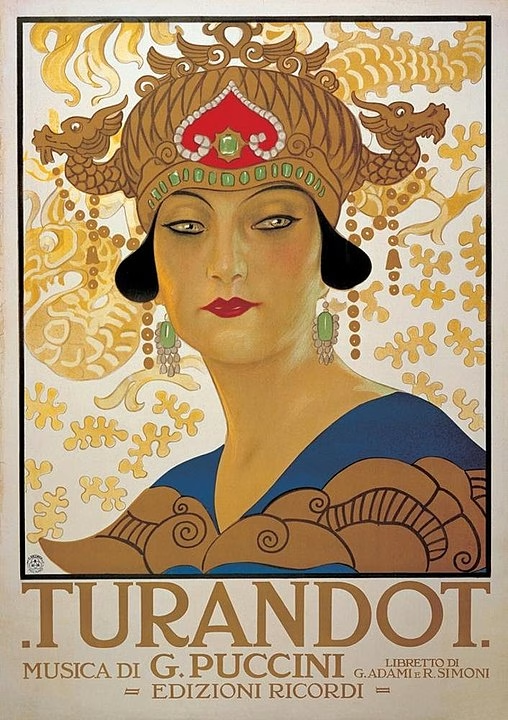

Turandot had its world premiere in Italy in 1924. Puccini and his Italian librettists Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni used a canonical story, which had been versioned for European stages several times over since the late 18th century. 1762 had seen the Venice premiere of Carlo Gozzi’s commedia dell’arte Turandot, inspired by François Pétis de la Croix’s collection of Persian fairy tales Les Mille et un Jours. The plays and operas about Turandot are typical Orientalist works built upon popular stereotypes of Chinese people and culture. The colonial society rarely recognised the innate value of foreign cultures or showed any interest in understanding them from the indigenous perspective. Even critics of colonialism who were genuinely fascinated by foreign cultures found it hard to cast off the prevailing ideology, which had Europe’s overwhelming superiority at its core.

The story of Turandot is about a Chinese princess who challenges her suitors: in order to marry the princess, they must answer three questions correctly. If they fail, they will be beheaded. The world of early 20th century European arts was full of such macabre adult fairy tales. The commedia dell’arte heritage of Gozzi’s original play is represented by the clownish characters of the ministers Ping, Pang and Pong, who serve as a stark contrast to the pitiable slave girl Liù and the monumentally sculpted lead couple Princess Turandot and Prince Calaf.

In Orientalist music, original songs from foreign cultures were either ruthlessly modified or completely fabricated.

Rather than being limited to the story, the exoticism of the time is also heard in the music of Turandot. Instruments associated with China and the varied role of the choir add to the fairy-tale ambience of the vibrantly orchestrated score. Pentatonic melodies, complex rhythms, and multifaceted harmonics built around sustained bass tones also known as pedal points create a radiant yet sombre imaginary landscape of the mythical Chinese past.

In Orientalist music, original songs from foreign cultures were either ruthlessly modified or completely fabricated. Puccini used several melodies of Chinese origin in Turandot. He had never been to China but knew a diplomat who had worked in the country. The diplomat gave him authentic Chinese source material, including a music box that played local hymns. The composer’s interest in Chinese culture was genuine, but it can’t be said that he was motivated by a desire to respect that culture. Puccini was fascinated by the idea of creating as authentic a milieu as possible, but his end result is in line with Orientalist art in general. The Oriental Other becomes a source of enjoyment and entertainment for the European audience. Chinese melodies have been adapted to western musical structures. Not only does a Chinese gong or xylophone bring about a Chinese atmosphere, but it also underlines the cruelty in the opera, bolstering the stereotype of the Chinese as violent barbarians.

Why should we discuss Orientalism today?

As a form of performing arts, opera has kept its place in modern society thanks to new interpretations. By digging deeper into the history of old operas, we can understand the societies in which they were originally created and which gave rise to their racist stereotypes. In her new version of Turandot, director Sofia Adrian Jupither wants to peel off the old layers of the performance tradition and focus on what makes the opera topical right now.

”Traditionally, Turandot has featured dated gender roles, misogyny, and racist stereotypes. It is particularly important for the future of the entire opera art form that these problematic themes are addressed, as that is the only way we can do something about them. This approach to Turandot is our humble attempt to find ways of making central works of operatic history viable in the modern day,” Jupither says.

Text PETRA RÖNKÄ & AULI SÄRKIÖ-PITKÄNEN

Performances of Turandot will take place in Finnish National Opera 27 January to 4 March 2023. Read director Sofia Jupither’s interview.