A man from a dream

The Horseman was the first opera for both composer Aulis Sallinen and writer Paavo Haavikko. In the Finnish arts scene, it marked a breakthrough with far-reaching consequences. Archaic in its power and resonant on many levels, The Horseman was received as a national milestone. Audiences and critics alike saw echoes of Finland’s fight for independence, as well as reflections of the political climate of the time. Yet at its core, The Horseman is a timeless story about power and freedom. Can a just society ever rise from the ruins of domination and exploitation?

Fifty years ago, the Finnish cultural landscape underwent a period of great transformation. In the summer of 1975, Aulis Sallinen’s The Horseman premiered at the Savonlinna Opera Festival. That same autumn, Joonas Kokkonen’s The Last Temptations had its world premiere at the Finnish National Opera. Together with Sallinen’s The Red Line, which premiered three years later, these works elevated opera to the forefront of Finnish art. In one bold leap, opera had become a powerful and relevant form of national expression.

What made these operas a watershed moment? After all, opera had been composed in Finland since the days of Sibelius and Melartin, and Leevi Madetoja’s The Ostrobothnians (1924) had already struck a deep chord with Finnish audiences. Yet opera composition had taken root slowly in Finland. This changed when the operas by Sallinen and Kokkonen found unprecedented success, both in Finland and internationally.

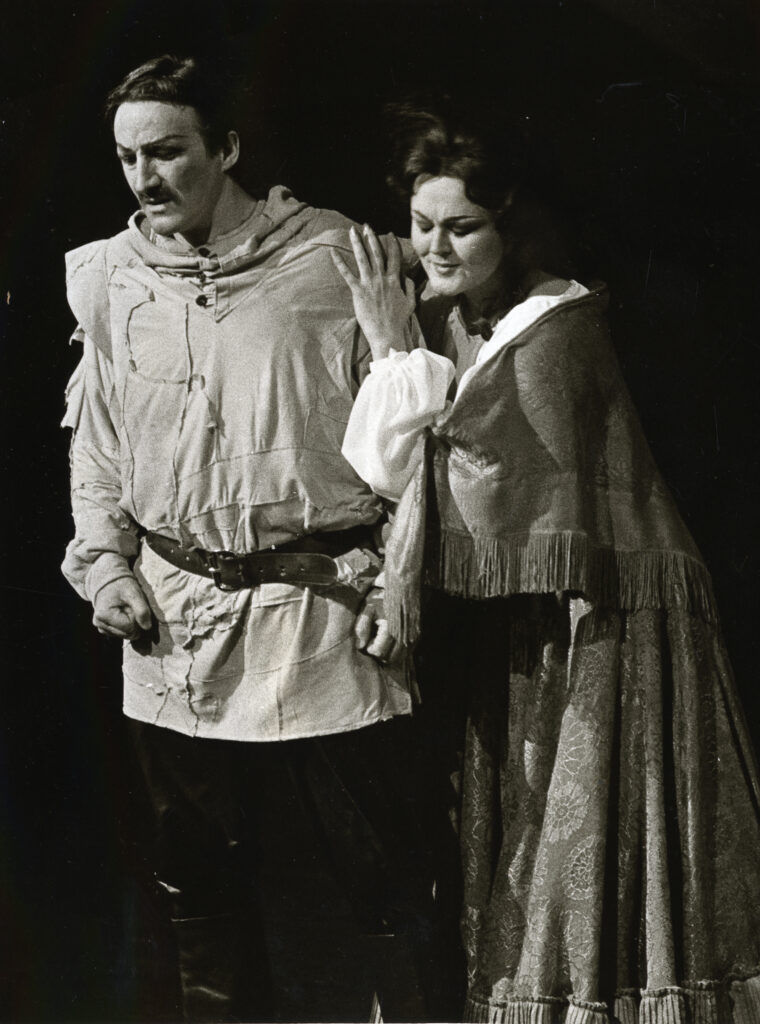

There were many reasons behind this phenomenon. These operas combined modern and traditional elements in original ways, blending timeless themes with social engagement. The moment was also ideal. The Savonlinna Opera Festival had been revived in 1967 after a long hiatus, and a new generation of exceptional singers had emerged. Among them were bass Martti Talvela (1935–1989), who served as Artistic Director of the festival during the 1970s, and soprano Taru Valjakka (b. 1938), who premiered the role of Anna in The Horseman. Bass Matti Salminen (b. 1945), who sang the title role, had just made his breakthrough on the international stage.

In his 1999 book Karvalakki kansakunnan kaapin päällä (“A fur hat atop a nation’s cupboard”), Mikko Heiniö writes that The Horseman, The Last Temptations, and The Red Line almost instantly reached the status of national monuments. A backlash followed just as quickly, with younger composers mocking them as backward “fur hat operas.” All three works are set in a modest, down-to-earth world, but what made them part of the Finnish national canon was less their actual content and more their reception.

During the Cold War, there was a strong demand for domestic art that could boost national confidence. According to Mikko Heiniö, Sallinen’s operas were discussed specifically as cultural exports that would help put Finland on the world map. Their role as identity symbols, and the “fur hat opera” label that Sallinen found irksome, have unfairly placed these operas within the tradition of Finnish national romanticism.

A defiant team

As an opera venture, The Horseman was bold and even provocative. The historical subject was chosen to mark the 500th anniversary of Olavinlinna Castle, for which the Savonlinna Opera Festival sought to commission a new work. Only two composers were invited to take part in the composition competition: Aulis Sallinen, who had recently gained recognition as a symphonic composer, and Bengt Johansson. The festival had earlier held a separate competition to find a suitable subject for the libretto.

Sallinen rejected all the suggested subjects, prompting some raised eyebrows within the committee. Instead, he approached poet and playwright Paavo Haavikko (1931–2008), who was immediately inspired by the challenge. At the time, both Haavikko and Sallinen were opera novices and not yet widely known. Without the Opera Festival’s invitation-only competition, Sallinen might never have become an opera composer at all. For The Horseman, this outsider’s perspective turned out to be a distinct advantage. In many ways, the opera became the breakthrough work for both Sallinen and Haavikko.

“Without the Opera Festival’s invitation-only competition, Sallinen might never have become an opera composer at all.”

Sallinen also brought on board Kalle Holmberg, a theatre director renowned for his social commentary. Both shared the conviction that in a compelling contemporary opera, each artistic element must stand independently while complementing the others. In The Horseman, theatrical influences are evident in the spoken word and shouted lines woven into the score.

Sallinen had a sharp instinct that Haavikko’s concise and enigmatic style, rich in symbolism, would suit opera perfectly. The Savonlinna Opera Festival committee, however, was appalled by the libretto. Some considered it morbid, and the entire project nearly came to a halt. Still, Sallinen stood firmly by his choice of librettist.

Symphonic theatre

Haavikko’s libretto played a major role in the success of The Horseman. At the same time, its poetic language, unprecedented in Finnish opera, was seen by some as difficult to grasp. Many earlier Finnish operas had stumbled over awkward librettos. For Sallinen, a good opera required a libretto with strong poetic expression, offering not realism but a kind of ambiguity that would feed the music.

The dominance of symphonic music had also slowed down the development of opera in Finland. Sallinen now brought together the traditions of orchestral music and theatricality to create a powerful operatic language. The Horseman was perceived as symphonic due to the strength of its musical structure. Its powerful fusion of vocal and orchestral writing even led some to describe it as a vocal symphony. Its intense orchestral sections simmer with unspoken emotions and dreamlike visions. Sallinen described The Horseman as a symphonic fresco, where text and music exist in mutually enriching dialogue.

“Haavikko’s libretto played a major role in the success of The Horseman.”

By 1970s standards, the musical language of The Horseman was strikingly eclectic. It boldly stretches from modern passages filled with percussion and tape recordings to Puccini-esque lyricism. Some critics described the score as patchy or incoherent. Pluralism, now more of a norm than an exception for composers, was still a new concept in Finland. One of The Horseman’s most enduring contributions was to demonstrate how contrasting musical styles could be successfully fused.

In his libretto, Haavikko structured each act of The Horseman as a largely self-contained entity, linked by recurring symbols: foretelling, forest, horse, and dream. These symbols, in turn, provided fertile ground for the opera’s core musical motifs. Among the most significant are the foretelling motif, introduced in the first act and played on bells, and the fate motif that weaves through the third act, derived from the Finnish folk song Aa aa allin lasta (“Hush, hush, eider chick”). The lullaby-like melody reflects the dream symbolism, while the bells evoke both Orthodox Easter chimes and ominous warnings. Both motifs foreshadow destruction.

Sallinen developed a remarkable command of vocal composition in his debut opera. During the writing process, he created a song cycle for Taru Valjakka titled Four Dream Songs, three of which appear at pivotal moments in the opera: the songs of Anna and the nameless woman in the courtroom scene, and Anna’s lullaby at the end of the opera. These passages serve as energetic focal points, drawing together and expanding upon the opera’s central themes.

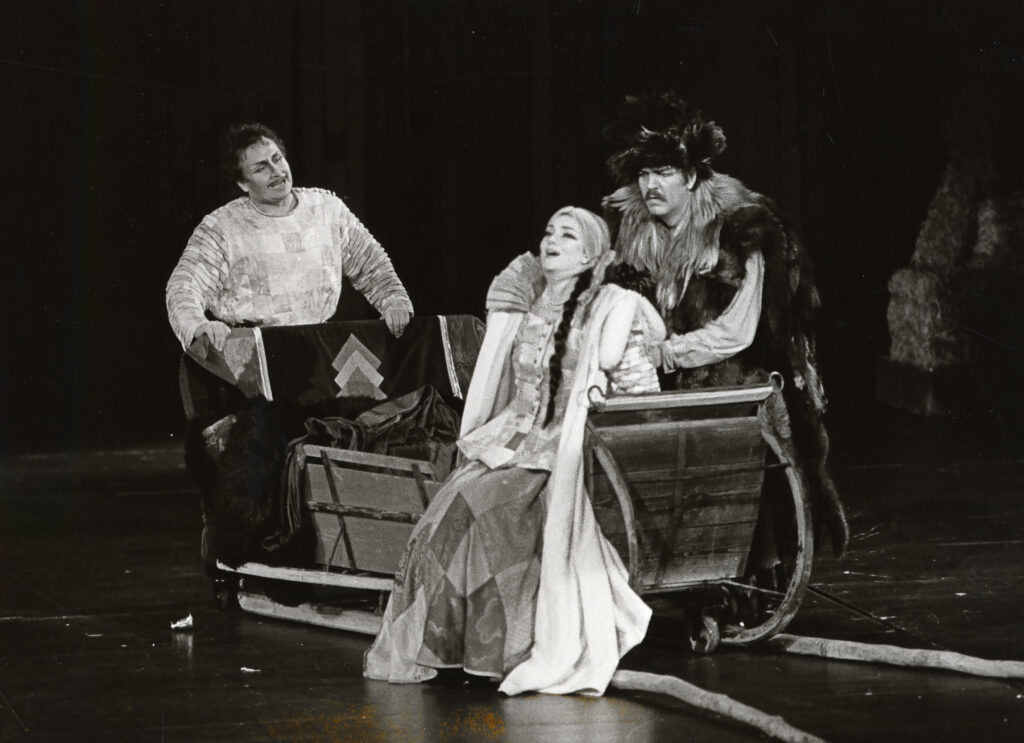

An opera about power

The historical backdrop of The Horseman is Olavinlinna Castle, built in the late 15th century on a volatile borderland where the Swedes and the people of Novgorod were in constant conflict. In the opera, however, Olavinlinna is not portrayed as a noble stronghold but as a prison and site of trials. The Novgorod Republic, one of the historical predecessors of the Russian Empire, had its capital some 200 kilometres south of present-day St Petersburg. As a result of these skirmishes, people from the Olavinlinna region were taken as slaves to Novgorod, while the King of Sweden sought to assert stronger control over the area. The royal manor of Liistonsaari featured in The Horseman really housed a sheriff and served as a base for soldiers.

Kalle Holmberg, who directed the world premiere, saw The Horseman as a revolutionary drama that distilled the history of Finland’s struggle for independence. At the time, the opera was viewed as containing political references to the Cold War and the re-election of President Kekkonen. For Sallinen, however, the tragic love story of Anna and Antti was more central. Haavikko, for his part, emphasised the layered nature of time in the work. Rather than historical realism, The Horseman offers symbolism. It can be interpreted as dreamlike and timeless, or as a work shaped by political philosophy.

“At the time, the opera was viewed as containing political references to the Cold War and President Kekkonen. For Sallinen, however, the tragic love story of Anna and Antti was more central.”

Haavikko once said that The Horseman presents “a theme and variations” on the relationship between a man and a woman. On a deeper level, however, it explores systems of power. This was a dimension he felt contemporary audiences largely overlooked. Today, The Horseman clearly stands out as a tale of power and its abuse.

Society in The Horseman is starkly divided: masters and slaves, a brutal authority and an oppressed working class. In the final act, a forest state is founded in the woods of Sääminki, built on a kind of anarchist utopia. Yet greed and exploitation soon begin to erode it. For people long accustomed to domination and violence, there is no existing model for what true equality might look like.

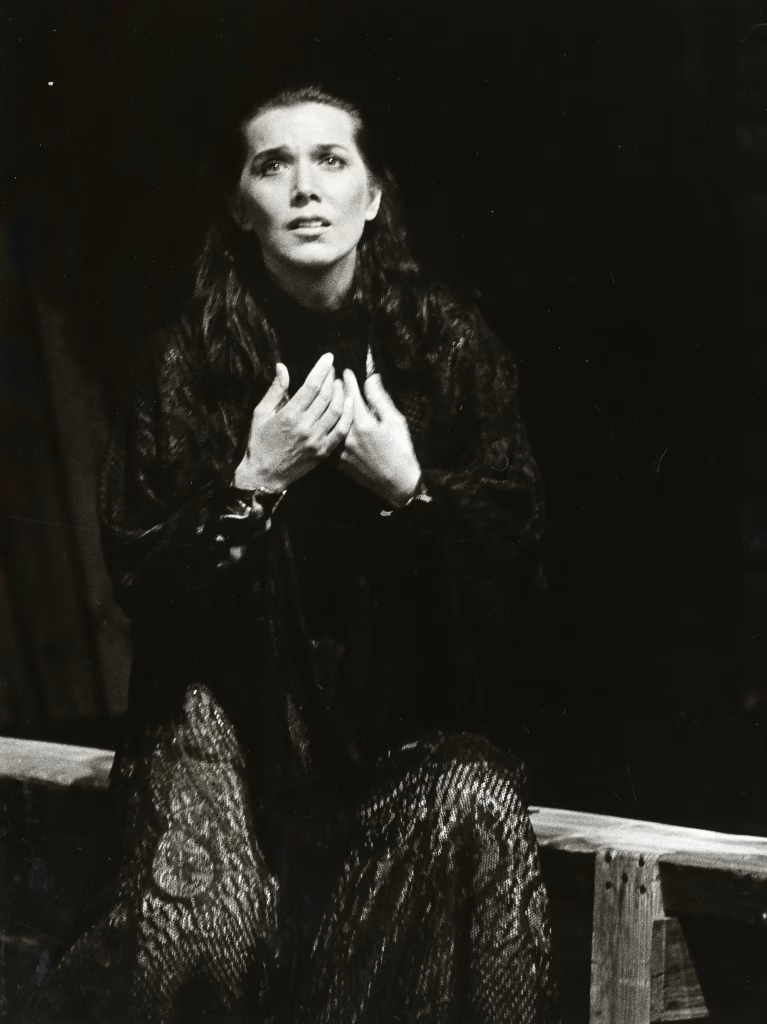

The world of The Horseman is steeped in physical and sexual violence. Women are treated as commodities to be owned, lent or shared. The Merchant and the Judge coerce their subordinates into sex, and the unnamed woman who stands trial pays a heavy price for her unwanted pregnancy. Within the forest community, sexual exploitation has been normalised in the name of freedom. But whose freedom is being served, and what price is paid to sustain this utopia?

The snares of foretelling

Bleak determinism is a hallmark of Haavikko’s work. People are powerless to alter their fate. In The Horseman, foretelling recurs throughout the narrative, ensnaring the characters in its web. Dreams, perhaps the most enigmatic of Haavikko’s recurring symbols, form another illusory net in which people struggle. Life itself is a dream, and the eyes open only at the point of death. “When the door of sleep does not want to open, its lock must be shot apart,” says the Horseman in his final moments.

At the same time, dreams offer protection from life’s deceptions, like a womb in which to safely slumber. Anna becomes a mother figure to her broken partner: “I will bury you in me again.” Antti is a Finnish Tristan, a doomed knight of sorrow who longs for death. Does this make Anna an Isolde figure, and does she ultimately find release and enlightenment? Despite their intense passion, the couple cannot overcome the weight of their trauma.

In the philosophy of Haavikko’s work, men are defined by forward movement, women by stillness. Yet the agency of men is full of contradictions. They are prisoners of fate who seek death, while women strive to preserve life. Anna and the unnamed woman attempt to negotiate and secure justice. The men in the opera, trapped in their fatalistic mindset, deny any moral responsibility. Antti launches an attack despite knowing it will lead to death: “Someone wants it. Thus it will happen.” It remains unclear who is responsible for the pregnancy that has led to the woman’s trial: Antti, the Judge, or perhaps the landowner? Such trials still occur today in countries where abortion is severely criminalised.

Rather than merely depicting binary gender roles, the opera’s sharply contrasted characters may be better understood as universal symbols of life and death. Their entanglement reveals the opera’s most profound meaning.

The scars of war

A Horseman is a military rank, and Antti is a former soldier. Whether he survived the war honourably or is a deserter remains unclear. Anna, who struggles to bring her unstable partner back to life, says towards the opera’s conclusion: “Thus from words grows war and war becomes truth.” In court, Anna passionately describes the loss of her husband, paraphrasing the well-known Finnish folk poem Jos mun tuttuni tulisi (“If My Friend Came Wandering”): “I would kiss his lips even if they dripped with wolf’s blood. I would hold his coat-sleeve if his hand were left in the wars.”

The Horseman can be interpreted as a portrayal of war trauma: the soldier returning from war has profoundly changed, turned away from life. With the loss of his horse, the horseman has lost his very identity. For Haavikko, a horse was often a sexually charged symbol, but in The Horseman it becomes a mediator between the realms of the living and the dead.

“The Horseman can be interpreted as a portrayal of war trauma.”

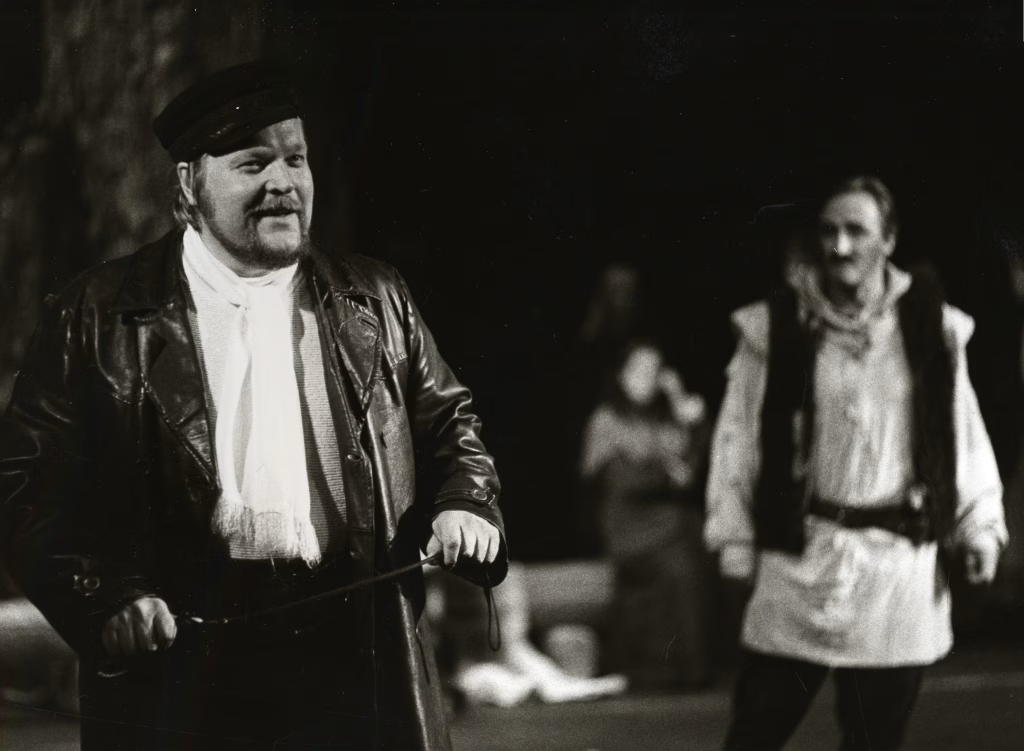

Dreams are also symbolic of loss, and the recurring references to the living mixing with the dead reflect a traumatised mind. Besides Antti, another troubled character is Matti Puikkanen, a murderer and wise-cracking fool who questions who truly holds power if everyone possesses it.

In the relentless inevitability dictated by foretelling, the dead haunt the living, who in turn sense their impending demise. Dream and reality are melded together in the bear ritual and the courtroom scene. Jarmo Anttila notes in his doctoral thesis, Aulis Sallisen Ratsumies ja Punainen viiva – Oopperaa, musiikkiteatteria ja kulttuuriradikalismia (“Ratsumies and Punainen Viiva by Aulis Sallinen. Opera, Music Theatre and Cultural Radicalism”, 2002), that the prophetic bear is not based on a genuine Orthodox Easter tradition. Instead, Haavikko combined elements from bear-hunting ceremonies and fertility rites into a powerful symbolic device.

Disguised as a bear, Antti foretells the Merchant’s death. In turn, the Merchant’s final words become an ominous act of foretelling, which Antti begins to fulfill: he will become the king of a moving forest, the free forest state. The rebels’ strategy of disguising themselves with tree branches recalls the familiar narrative motif of a moving forest, best known from Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

The opera’s prologue, a hymn for male chorus, is not a direct musical quotation. Instead, Sallinen combined elements of Orthodox church singing with randomly constructed syllables from Russian words. Thus, the chorus evokes Novgorod, historically renowned for its church choirs, and transforms into a hallucinatory, dream-like voice.

Text Auli Särkiö-Pitkänen

The writer is a poet and freelance music writer.

Translation Anna Kurkijärvi-Willans

Photos Kari Hakli

Recommended for you

Morgonstjärnan – The Morning Star: the director’s perspective

Morgonstjärnan – The Morning Star: The creators of the visual world

Morgonstjärnan – The Morning Star: how the opera's music was born

The Horseman

Hansel and Gretel

The perfect revenge?

CircOpera 2.0: towards the premiere