From the start of the new millennium, the Finnish National Ballet was headed by Nordic directors for more than 20 consecutive years. Dinna Bjørn from Denmark was the artistic director from 2001 to 2008. She was succeeded by a fellow Dane, Kenneth Greve, from 2008 to 2018, and from 2018 to 2022 Madeleine Onne from Sweden took the helm. The ballet finally gained equal status with the opera under Greve’s leadership.

A new leader from Denmark

The long streak of Finnish directors at the Finnish National Ballet ended in 2001 with the appointment of Dinna Bjørn from Denmark. She had previously been the director of the Norwegian National Ballet in Oslo for more than 10 years. While working as a dancer at the Royal Danish Ballet, Bjørn had discovered the work and technique of August Bournonville, who was much admired in Denmark. She later became an internationally renowned teacher, rehearsal director and lecturer of the Bournonville technique. During Bjørn’s tenure, however, Napoli was the only ballet by Bournonville seen at the Finnish National Ballet.

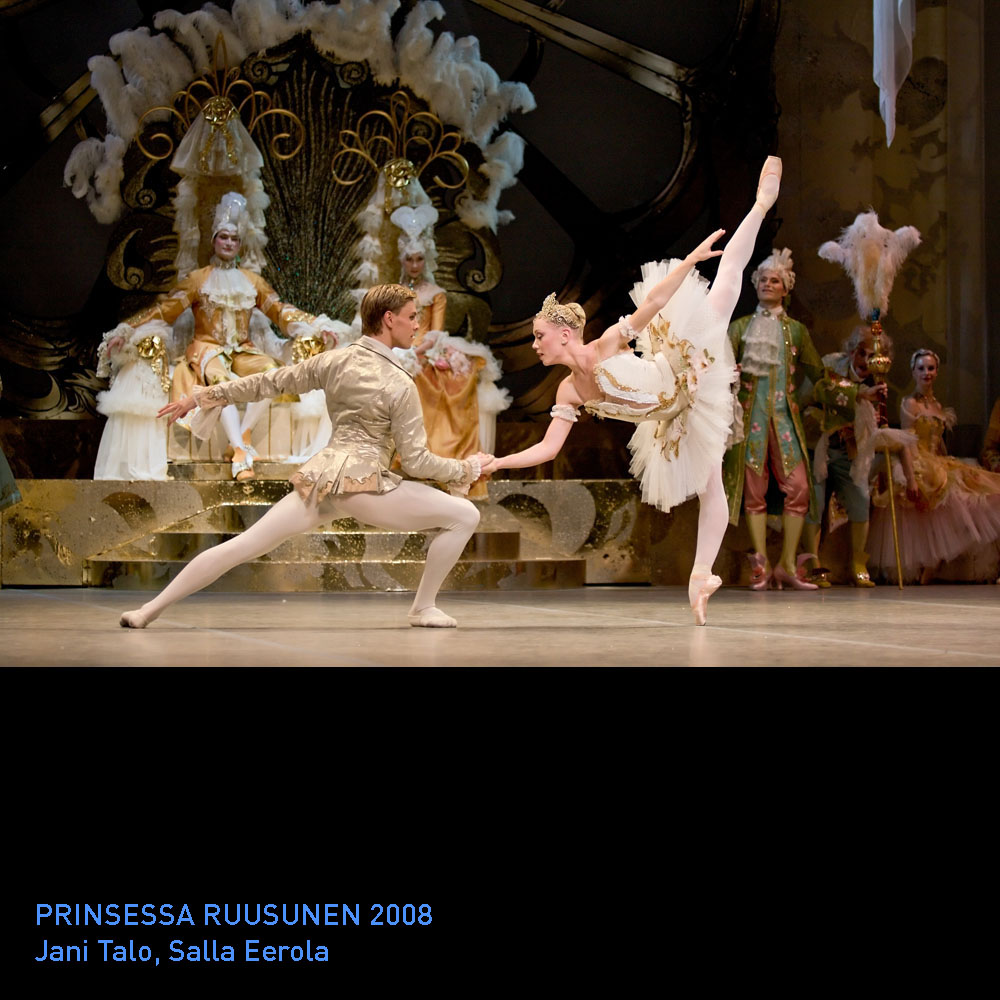

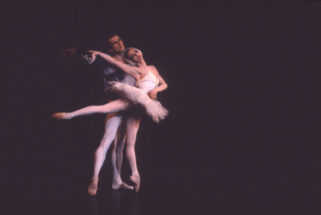

Bjørn maintained the ballet company’s existing repertoire pattern, with full-length classical ballets complemented by an evening of three contemporary dance works on the Main Stage and minor productions at Almi Hall. Early in her tenure, in 2002, she introduced Toer van Schayk and Wayne Eagling’s version of The Nutcracker and the Mouse King to the repertoire. It became a huge success for the festive period, with sold-out performances nearly every year over the last two decades. Another classic that has stayed in the repertoire since Bjørn’s tenure is Javier Torres’s version of The Sleeping Beauty from 2008.

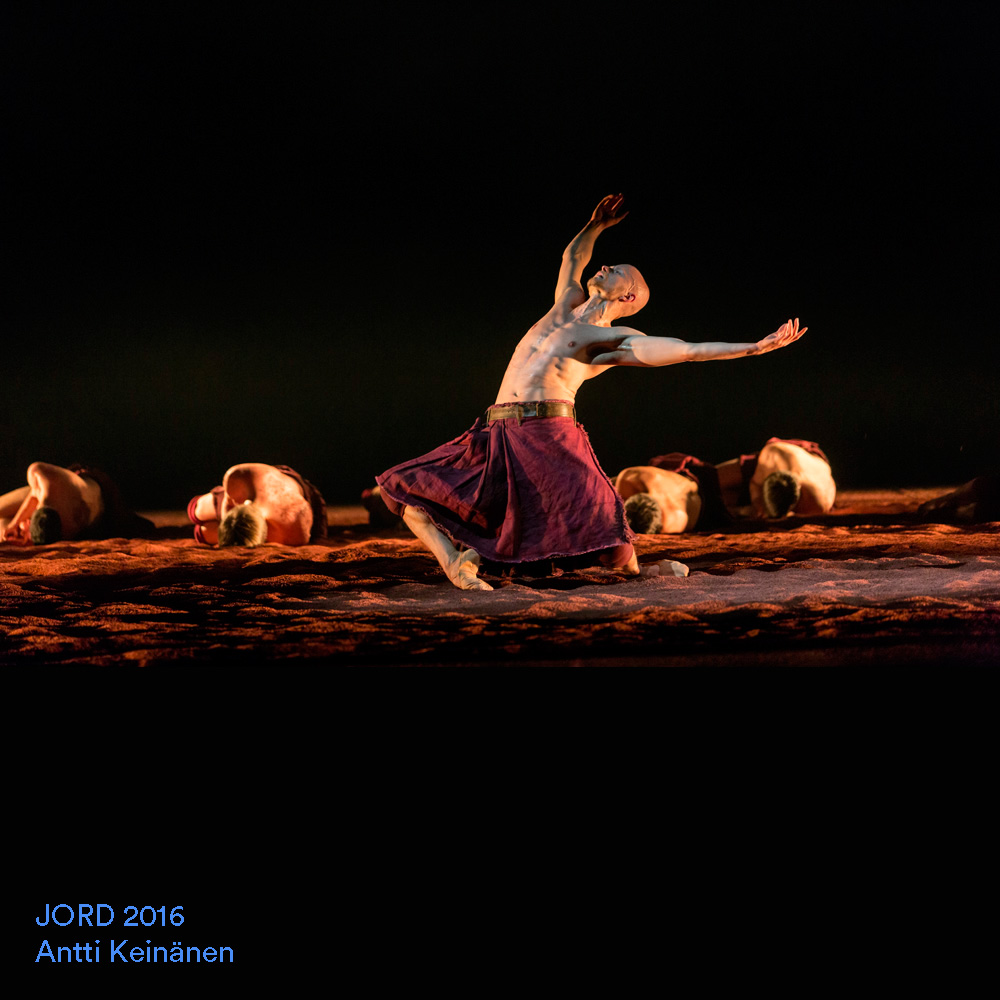

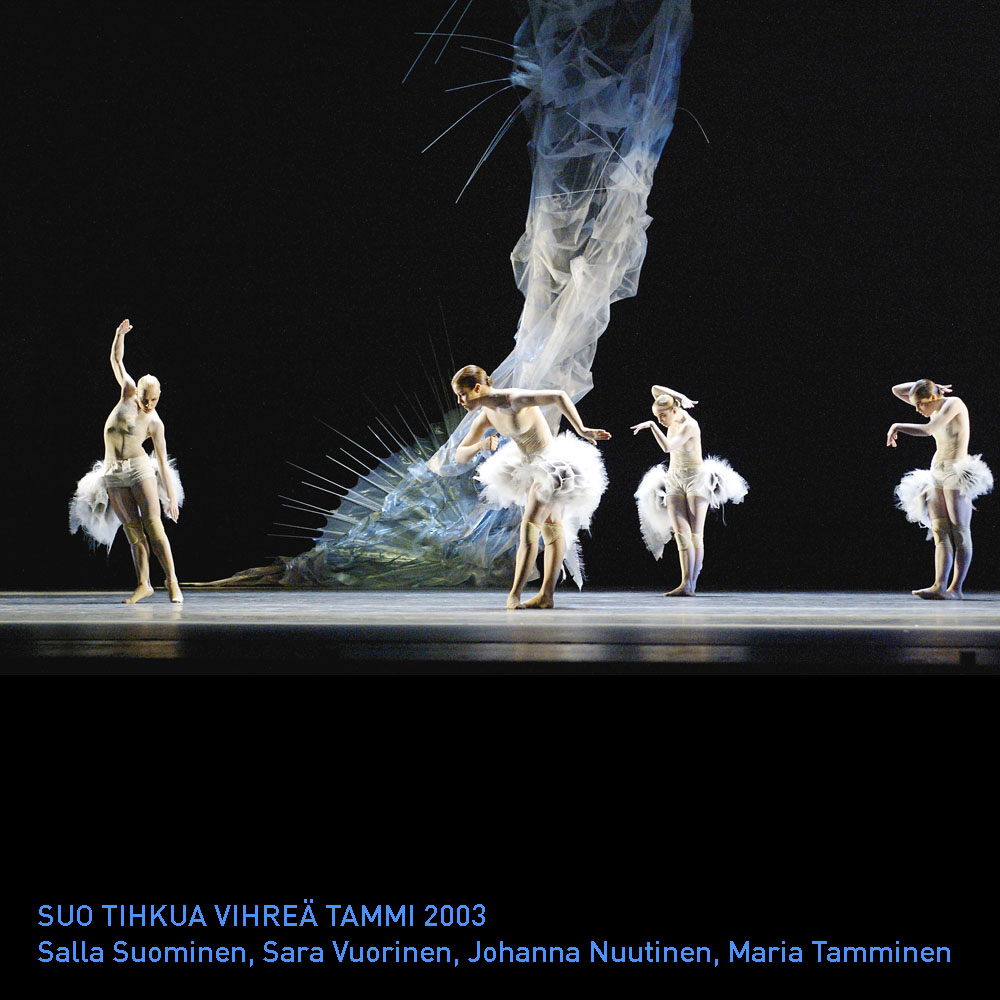

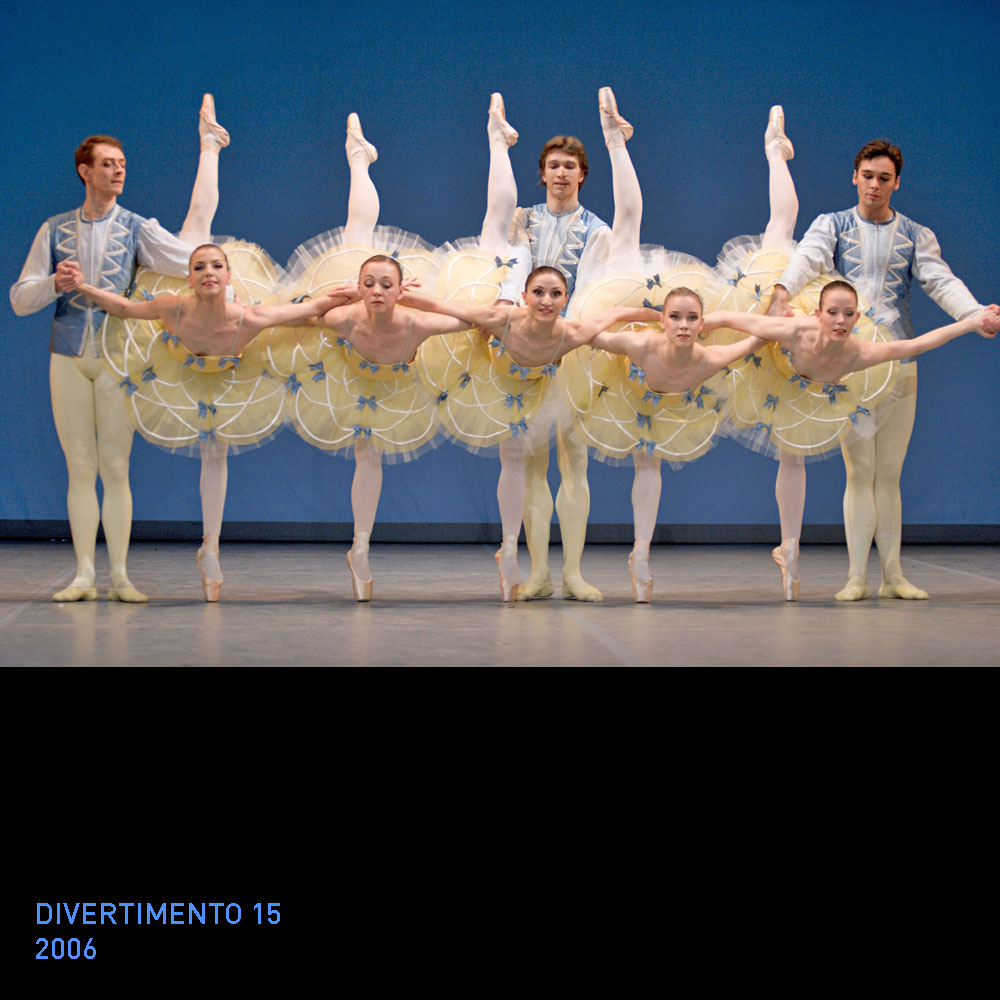

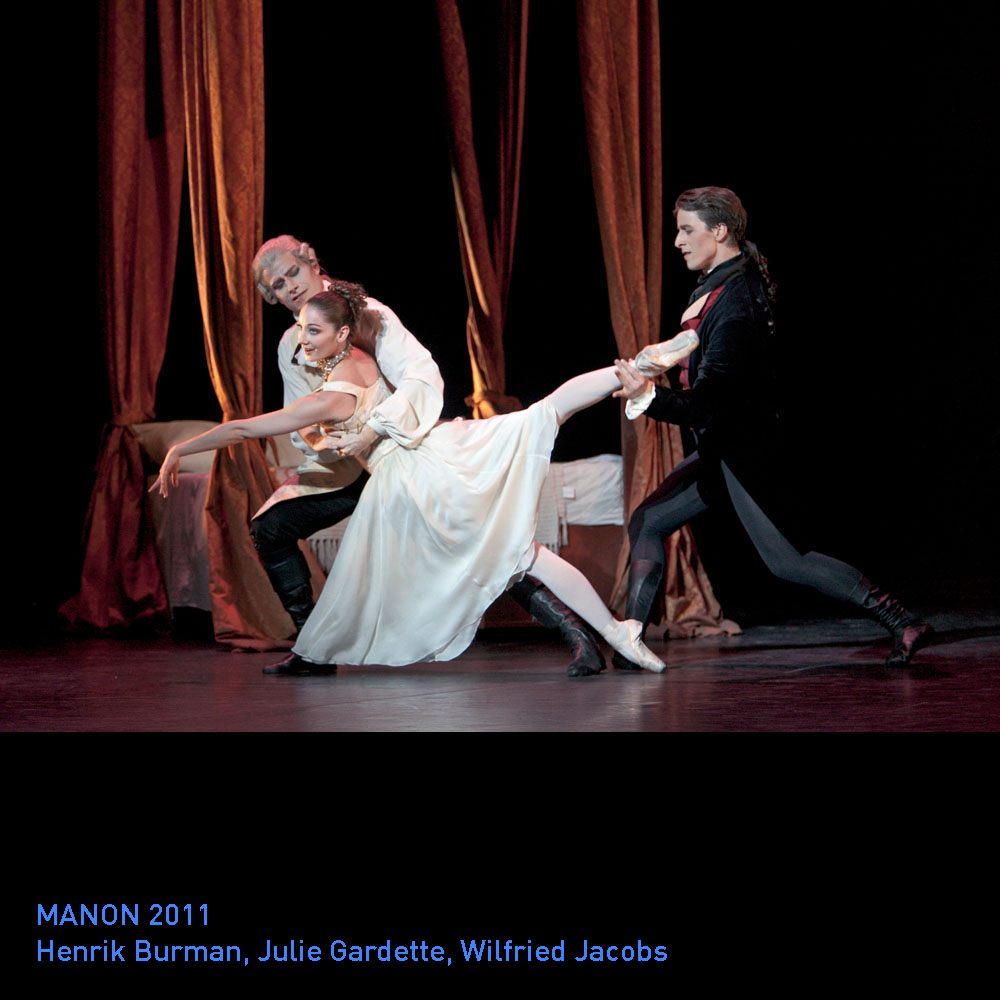

In addition to classic works, the repertoire comprised productions from the world’s leading choreographers, such as John Neumeier, Jiří Kylián, George Balanchine and Alexei Ratmansky. Ratmansky’s Anna Karenina became a lasting favourite at the Finnish National Ballet. Many Finnish choreographies were also seen on the Main Stage and at Almi Hall, including works by the internationally renowned Jorma Elo and Tero Saarinen.

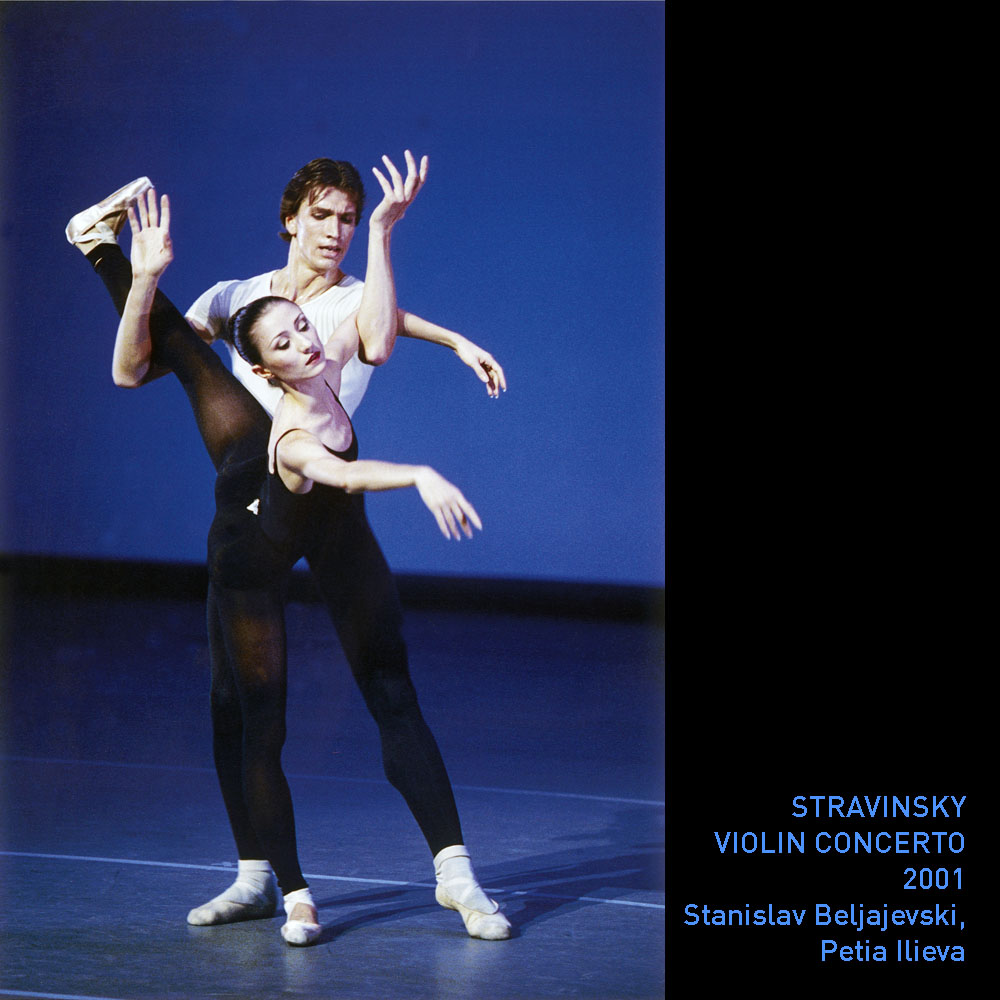

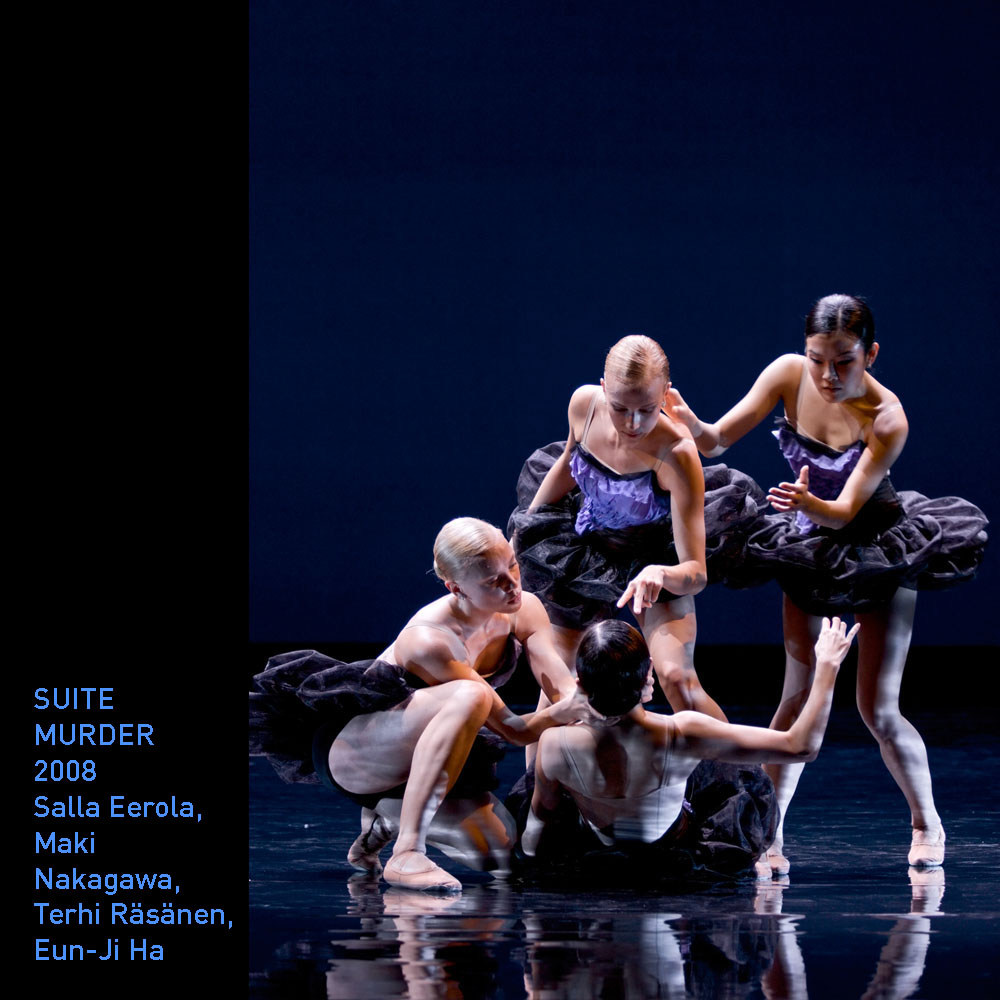

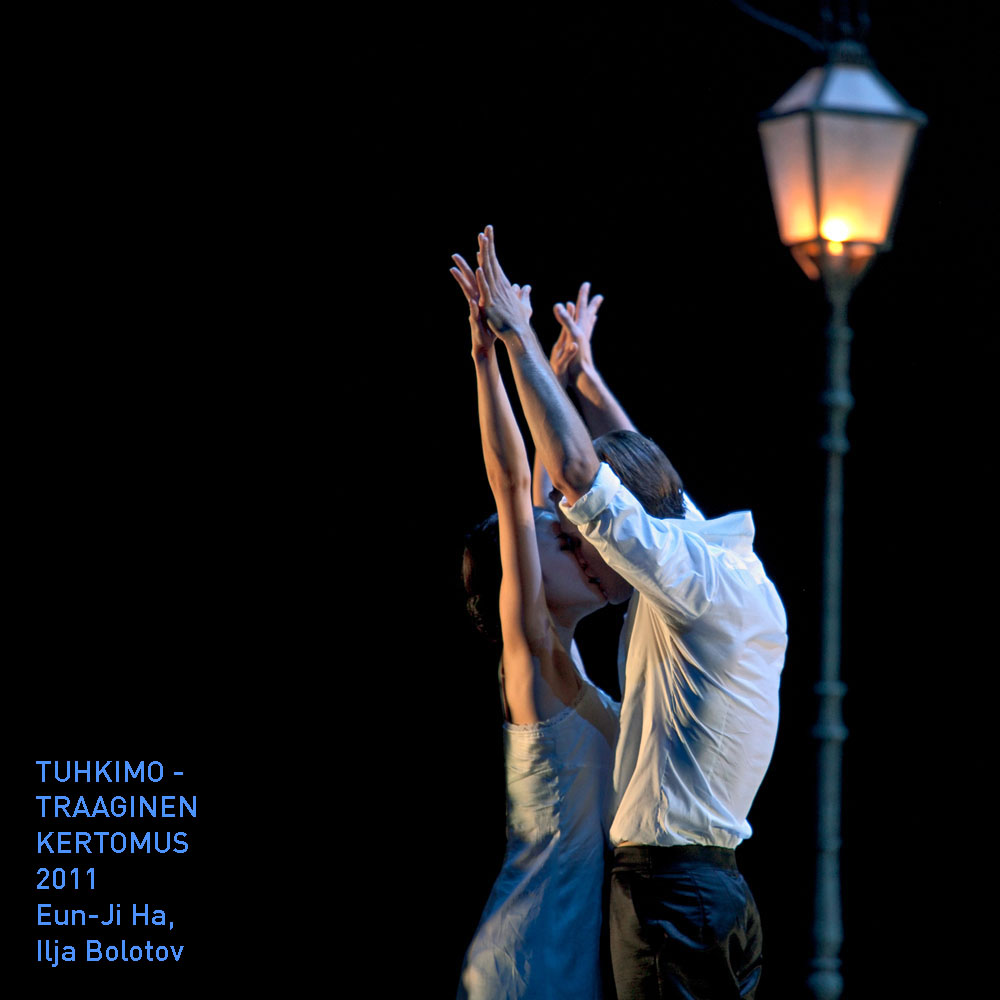

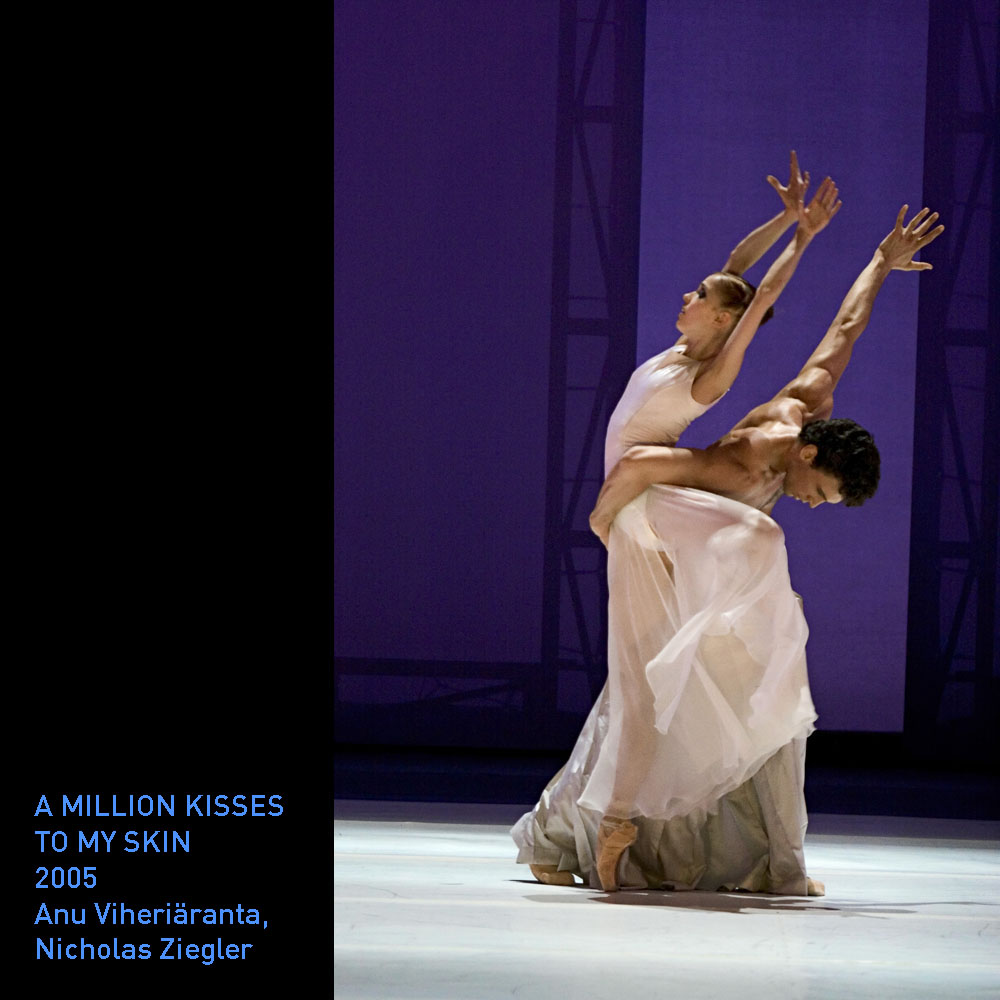

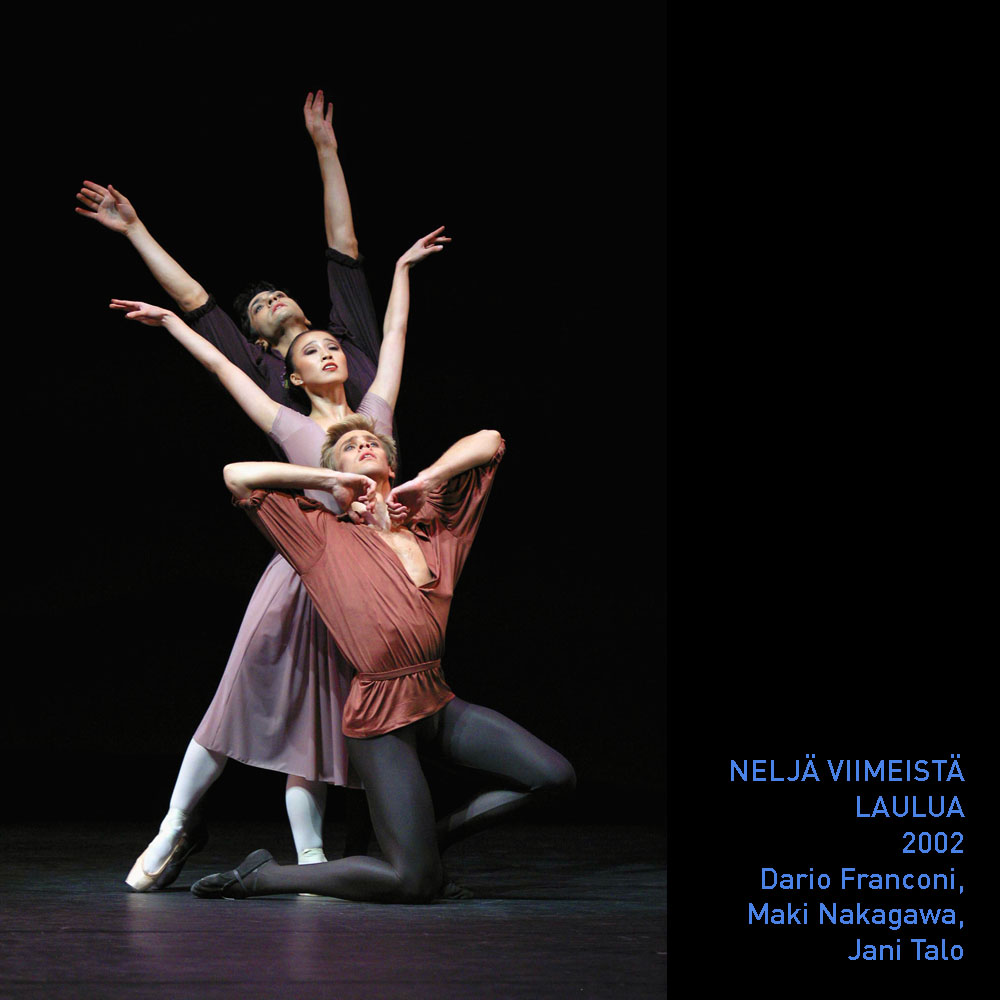

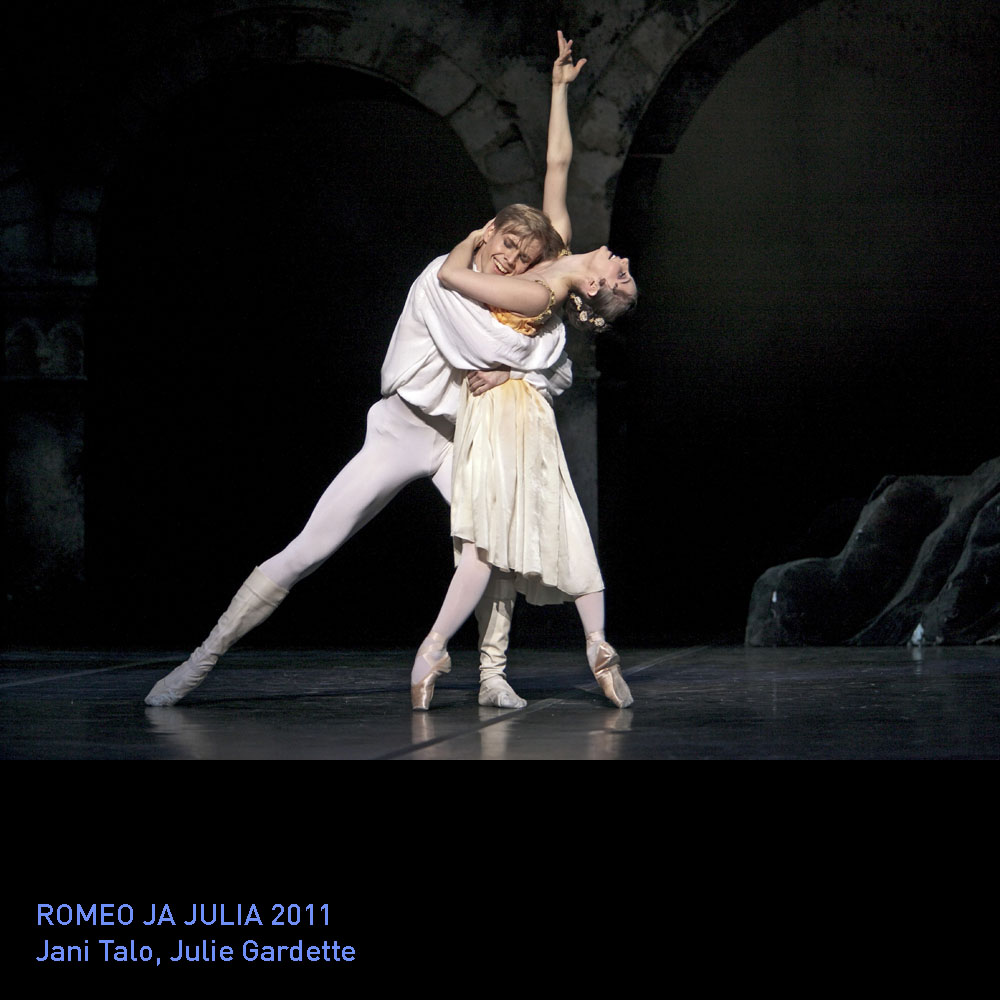

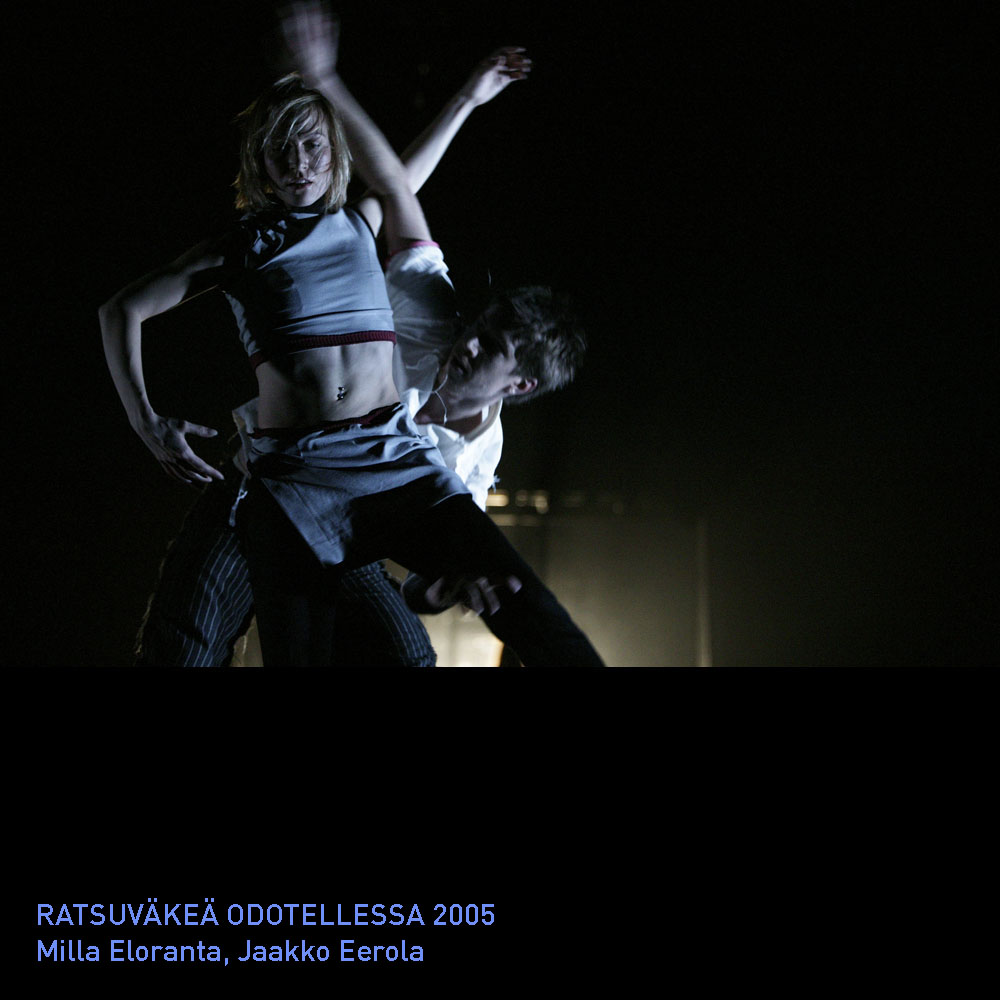

Bjørn’s tenure brought growing fame to young dancers such as Salla and Jaakko Eerola, Anu Viheriäranta and Jani Talo. The ballet company also attracted international talent like Nicholas Ziegler, Stanislav Beljajevski, Petia Ilieva, Eun-Ji Ha, Carolina Agüere and Dario Franconi, who were seen in many lead roles.

Ballet finally catches up with opera

Ballet had typically been considered subordinate to opera ever since the genre was born, as it was initially just an art form that supported opera. This was still evident at the start of the millennium in Finland, though the ballet company already operated more or less separately from the opera company, and ballet dancers only very rarely participated in opera performances. The underappreciation of ballet was manifest in the dancers’ lower salaries and worse employment conditions compared to the singers, and in the director of the ballet reporting to the director of the opera.

Doris Laine was already striving for more independence for the ballet during her tenure, but as that failed to materialise, she gave up her position and left to head the ballet of the Komische Oper in Berlin. Dinna Bjørn, too, struggled with the same challenge, as opera and ballet shared a budget, over which the general director and artistic director of the opera Erkki Korhonen had the final say.

Towards the end of Bjørn’s tenure, in 2007, the financial hardships of the Finnish National Opera led to changes that also affected the ballet. Päivi Kärkkäinen was appointed as the general director from outside the world of opera, and the artistic directors of both opera and ballet reported to her. That meant ballet had finally gained its independence, both in terms of financing and personnel. The new board of directors was completed the following year with the appointment of Kenneth Greve as the artistic director of the ballet.

Greve continued to drive the improved status of the ballet, starting the discussion over the name of the institution. Until then, the ballet company had operated first under the Finnish Opera and then the Finnish National Opera, and though it had been referred to as the National Ballet, it was still part of the National Opera. In 2015 the official name of the institution finally became the Finnish National Opera and Ballet, of which the National Opera and National Ballet were equal parts.

Assigning dancers etoile and soloist titles had been stopped at the Finnish National Ballet at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s. Most dancers liked the equality of this system, but Dinna Bjørn saw its challenges, for example as guest choreographers wouldn’t instantly know who were the group’s key dancers. Neither could the most accomplished dancers call themselves etoiles and soloists, as was the international custom.

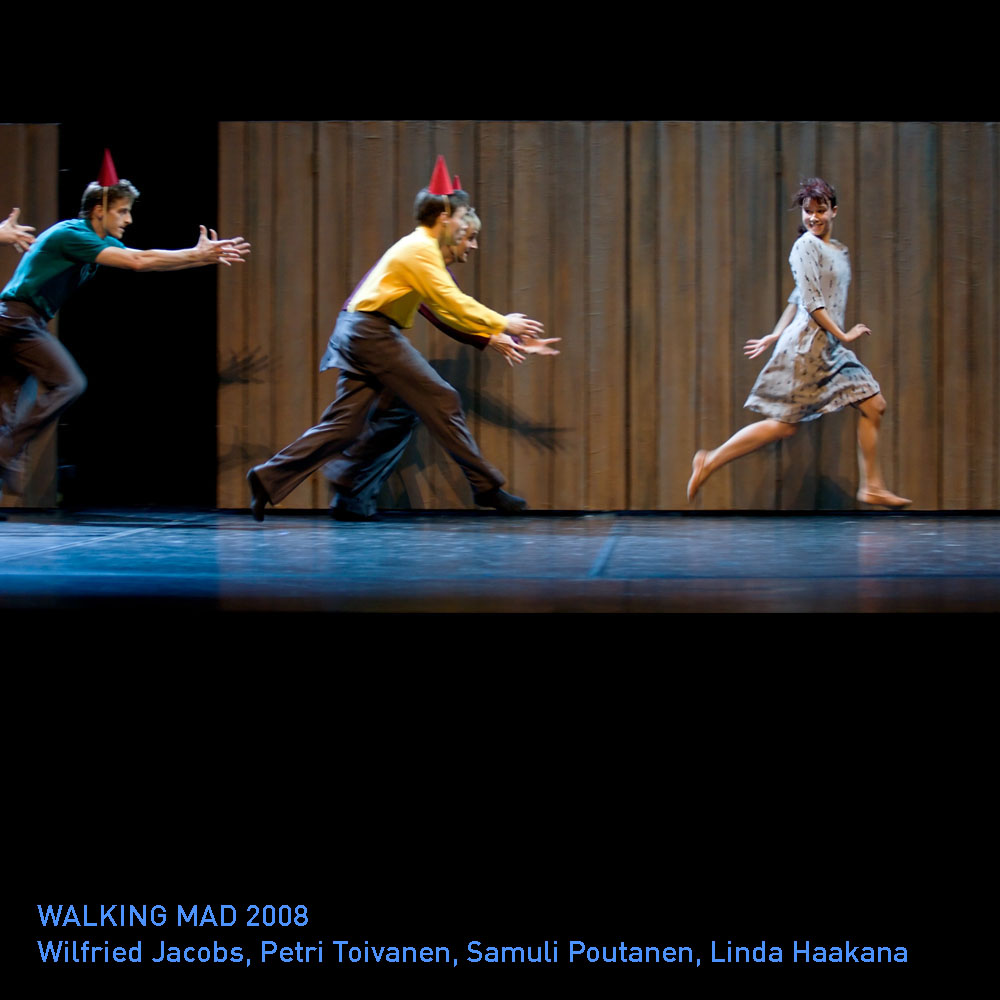

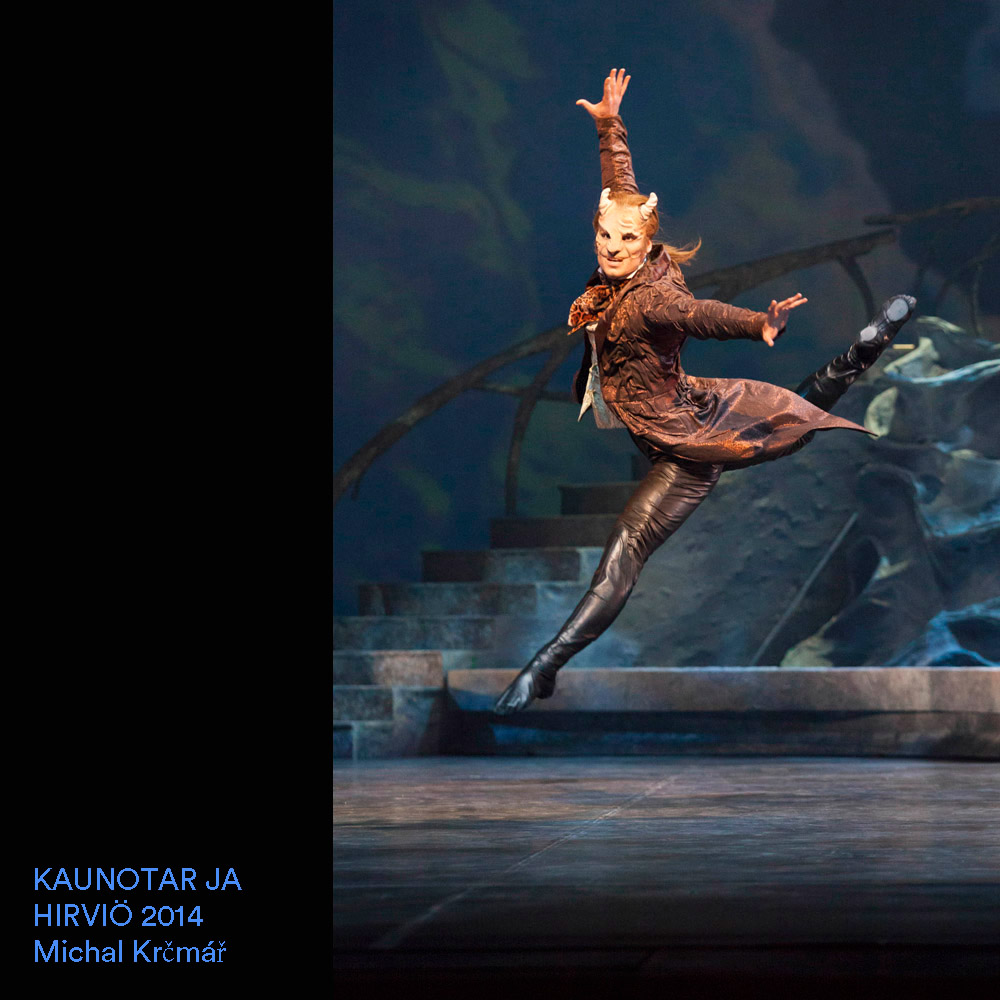

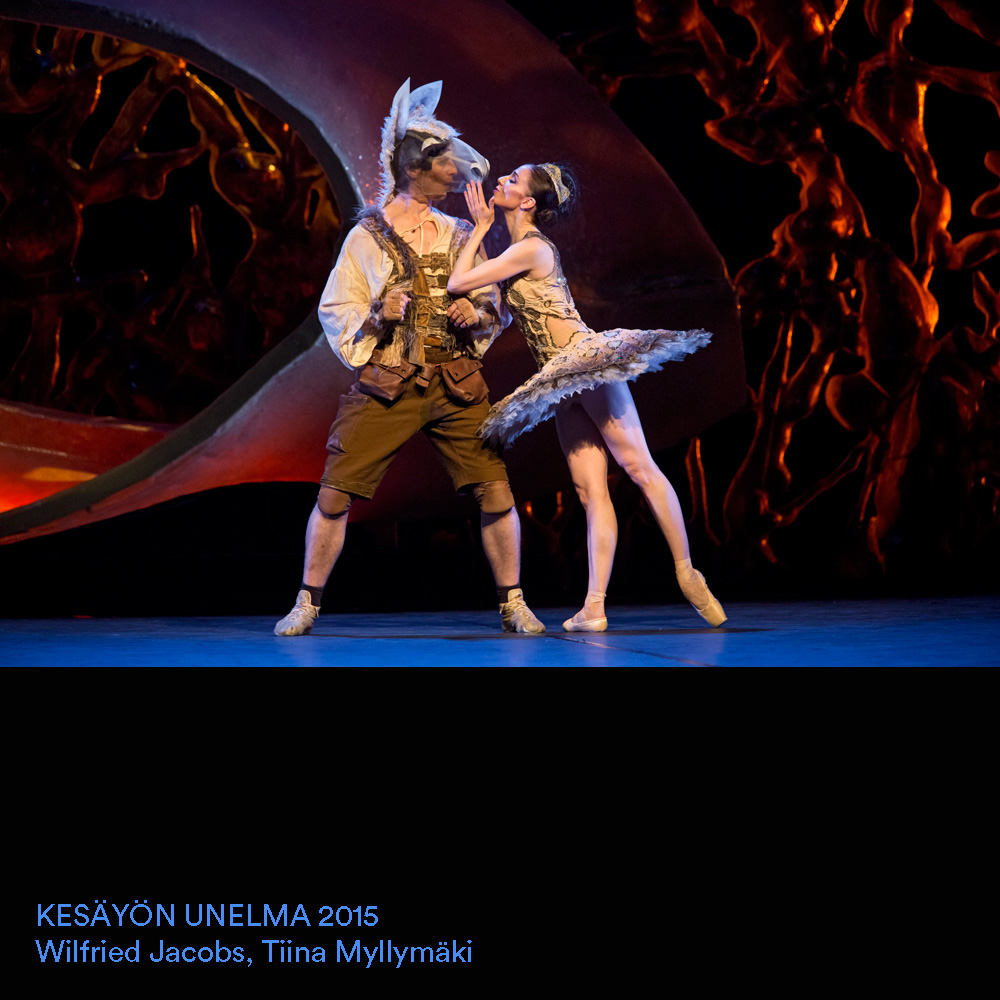

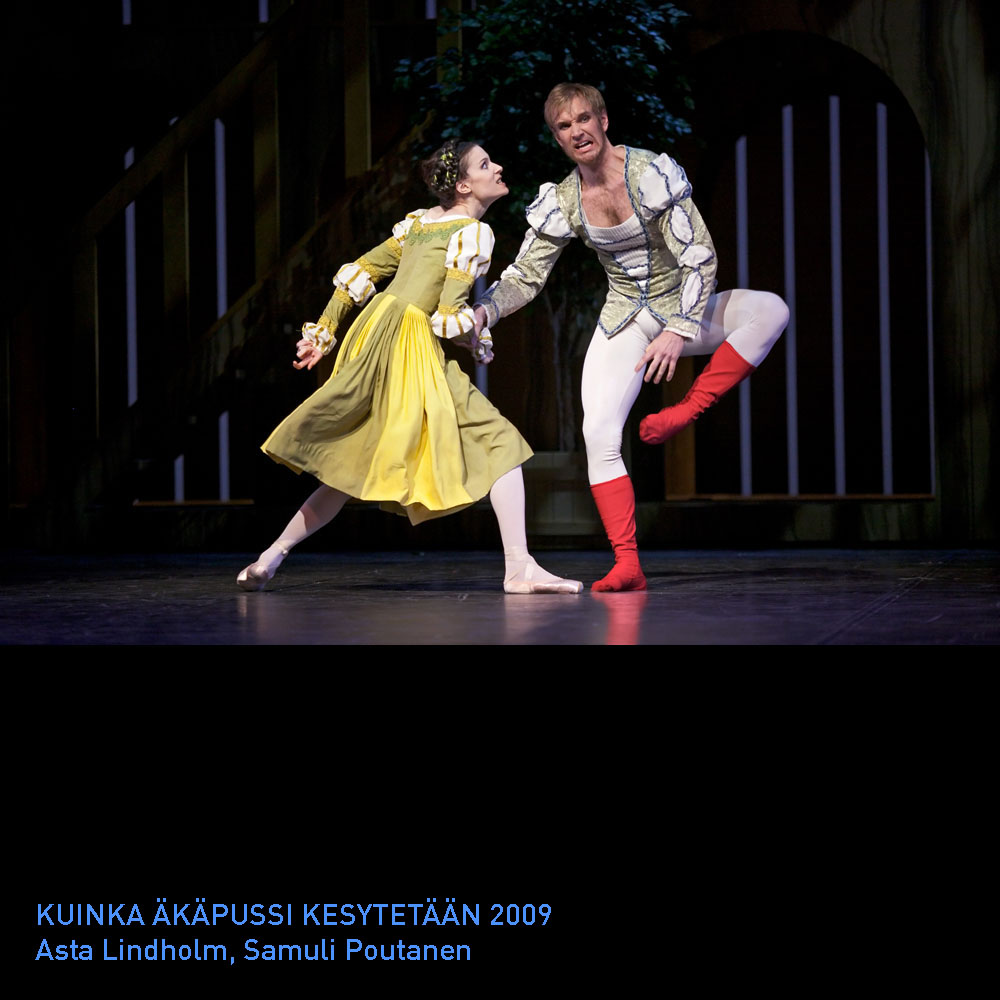

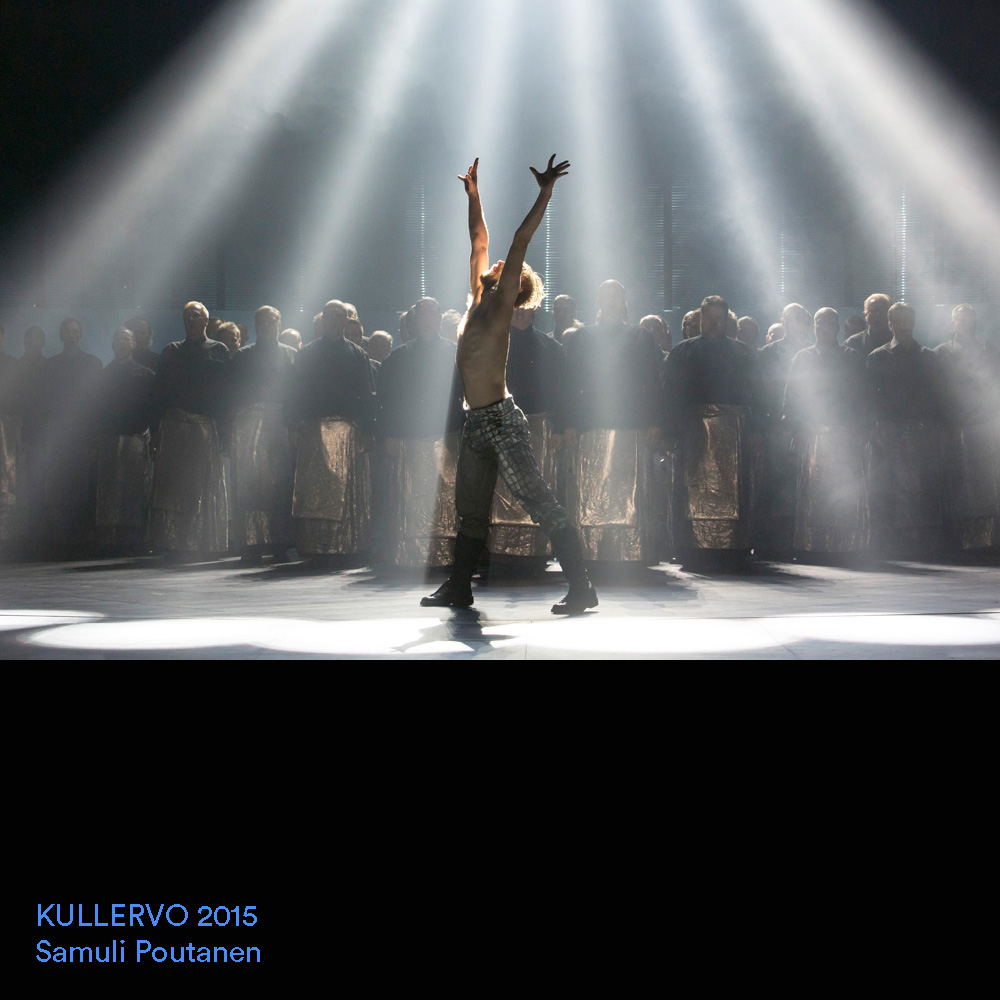

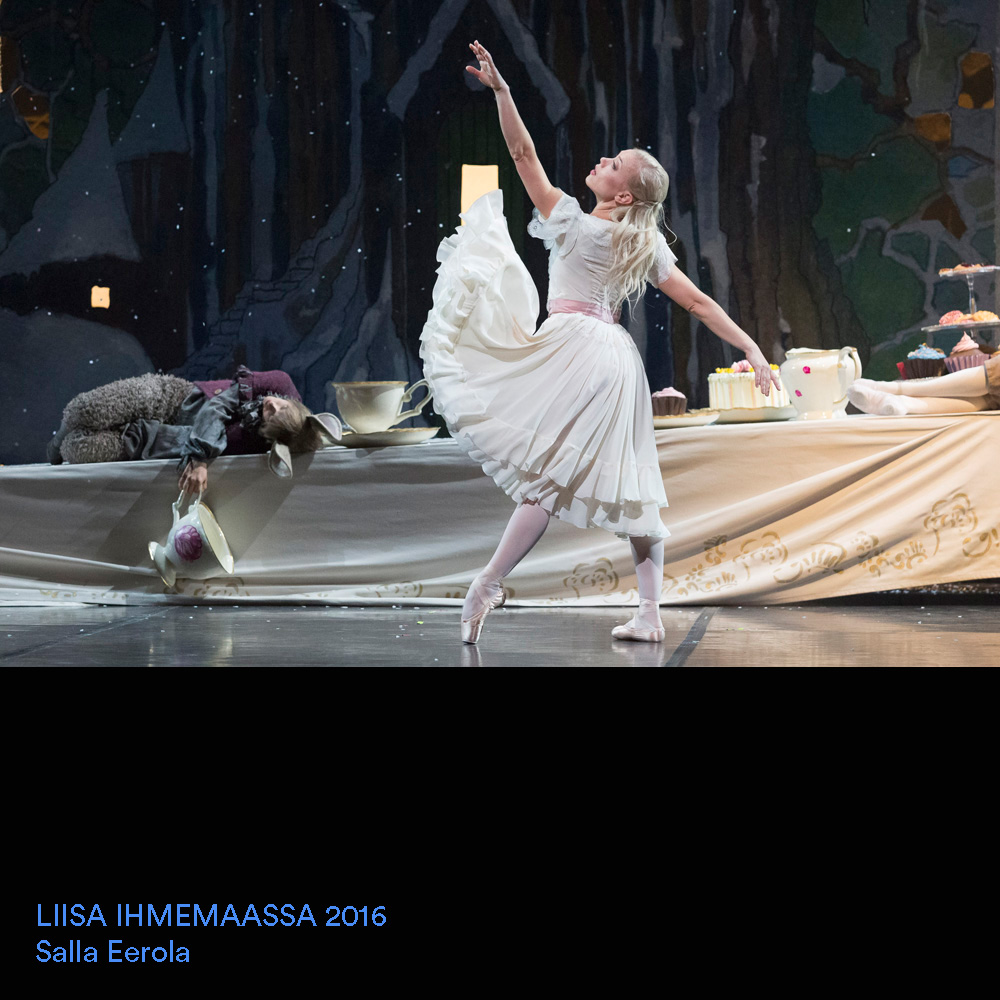

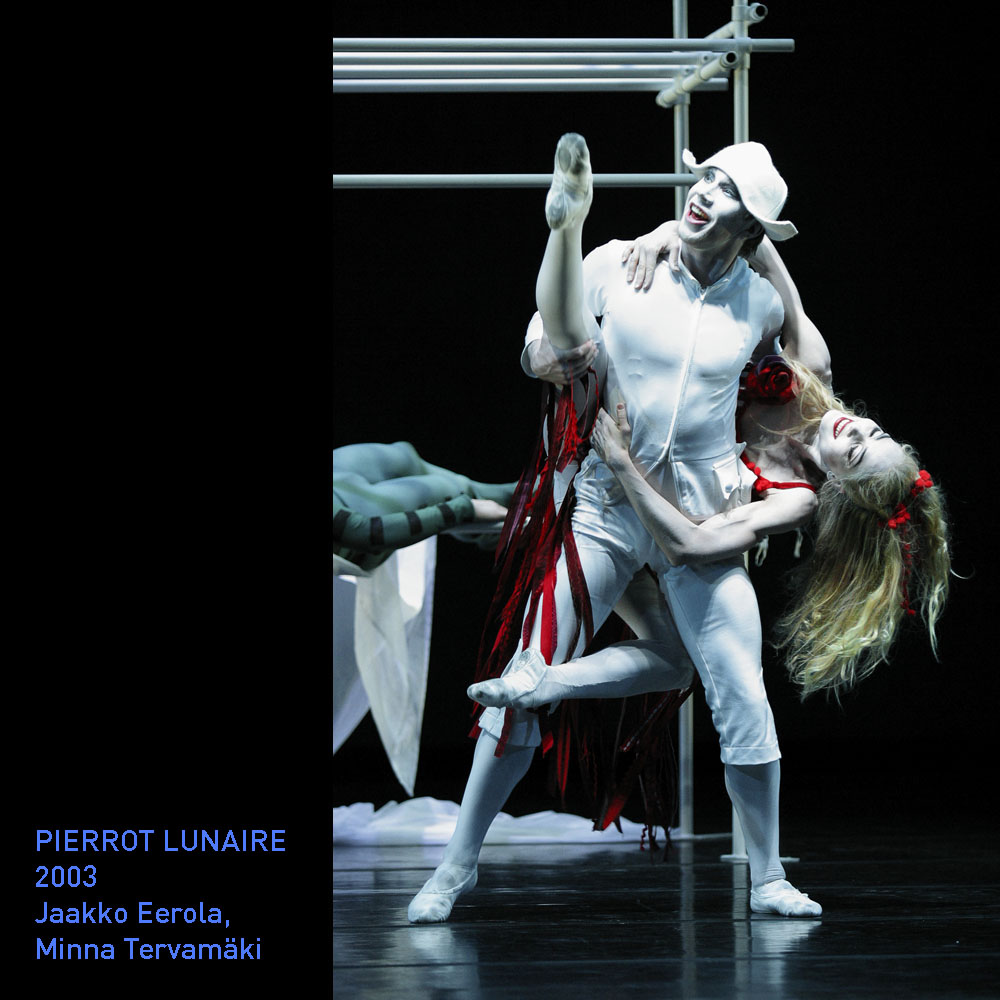

Kenneth Greve brought the titles back to the Finnish National Ballet, making Minna Tervamäki an etoile dancer in 2009. Additionally, the etoile title was given to Petia Ilieva, Jaakko Eerola, Salla Eerola, Nicholas Ziegler, Samuli Poutanen, Eun-Ji Ha, Michal Krčmář, Tiina Myllymäki and Sergei Popov. His new hierarchy included etoiles, principal dancers and soloists, but under Madeleine Onne’s leadership the etoile title was abandoned and soloists were divided into first and second soloists.

Successful ballet spectacles

Bjørn’s successor, the former ballet master of the Royal Danish Ballet Kenneth Greve, was also Danish. In many ways he was the opposite of his predecessor, as unlike Bjørn with her extensive director experience, Greve took on the role of a ballet director for the first time. While Bjørn filled the repertoire with works from other choreographers, Greve himself choreographed a whole host of premieres for the Finnish National Ballet. The energetic Greve proactively launched new activities for the ballet and enhanced its profile via different events.

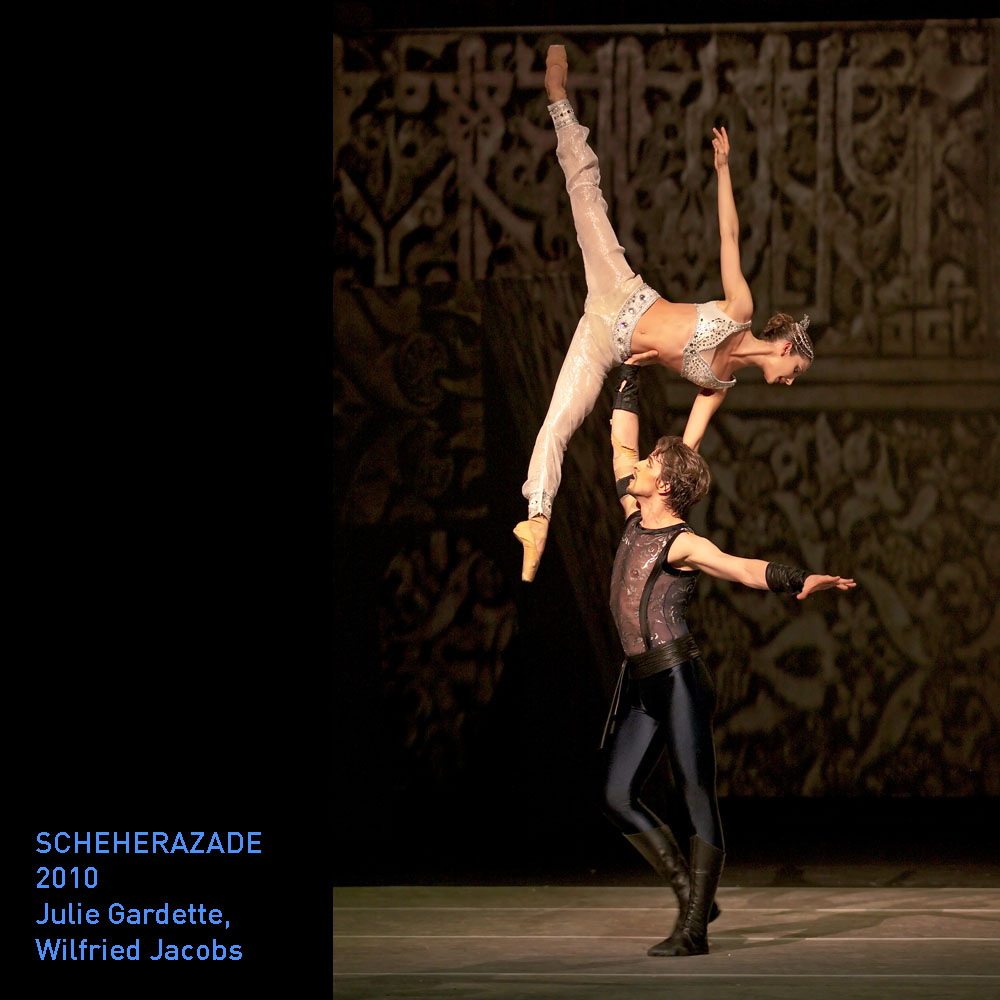

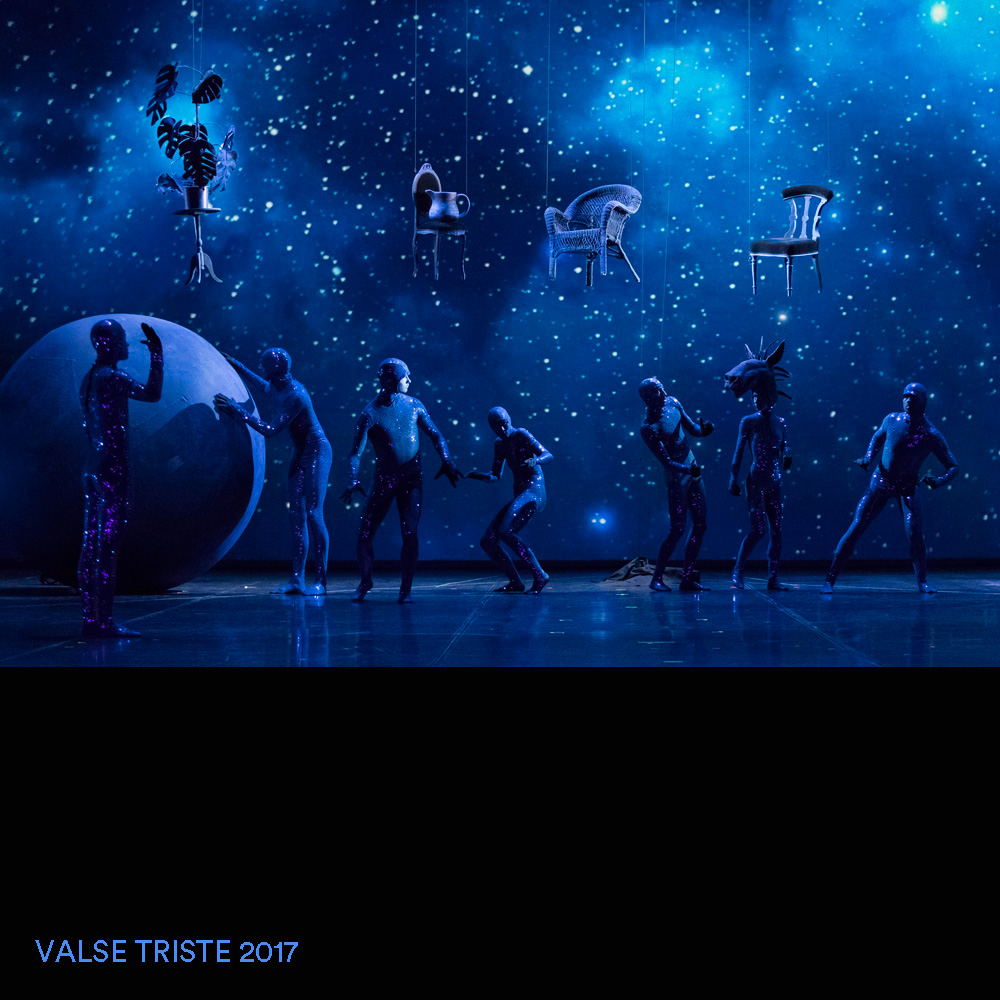

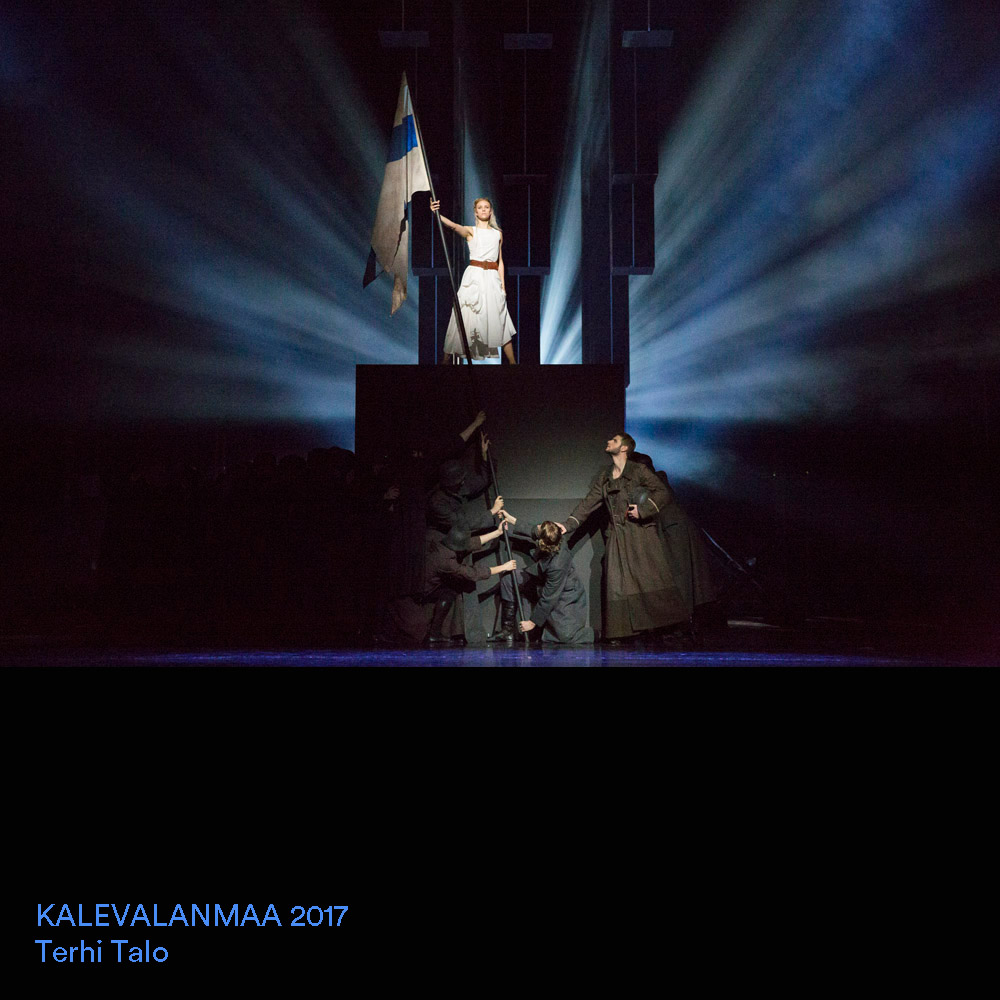

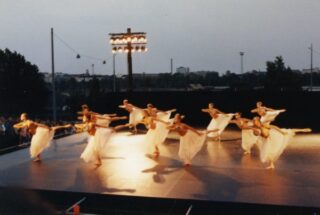

The favourites of the repertoire during Kenneth Greve’s tenure were his own choreographies, which often combined elements uncommon to traditional ballet performances. In The Snow Queen, for example, there was a narrator, the grandmother performed by etoile Minna Tervamäki alongside many leading Finnish actors. The folk dance group Värttinä, accordionist Kimmo Pohjonen and the Chorus of the Finnish National Opera were seen onstage in The Land of Kalevala. Two of Greve’s works, The Snow Queen and The Little Mermaid, were based on stories by his compatriot H.C. Andersen, while Swan Lake and Scheherazade were new versions of traditional ballets. The Land of Kalevala was a pioneering medley of scenes from Finnish history to Finnish music, and Moomin and the Magician’s Hat was a shorter, family-oriented ballet created with the Japanese tour in mind. Tuomas Kantelinen composed the music for many of Greve’s choreographies.

In the 2010s more works from other opera companies were brought into the repertoire, with the costumes and sets rented for the Finnish National Ballet. This enabled more premieres without excessive effort for the in-house costume and set workshops. Renting productions also helped save costs when performing a ballet for just one short season.

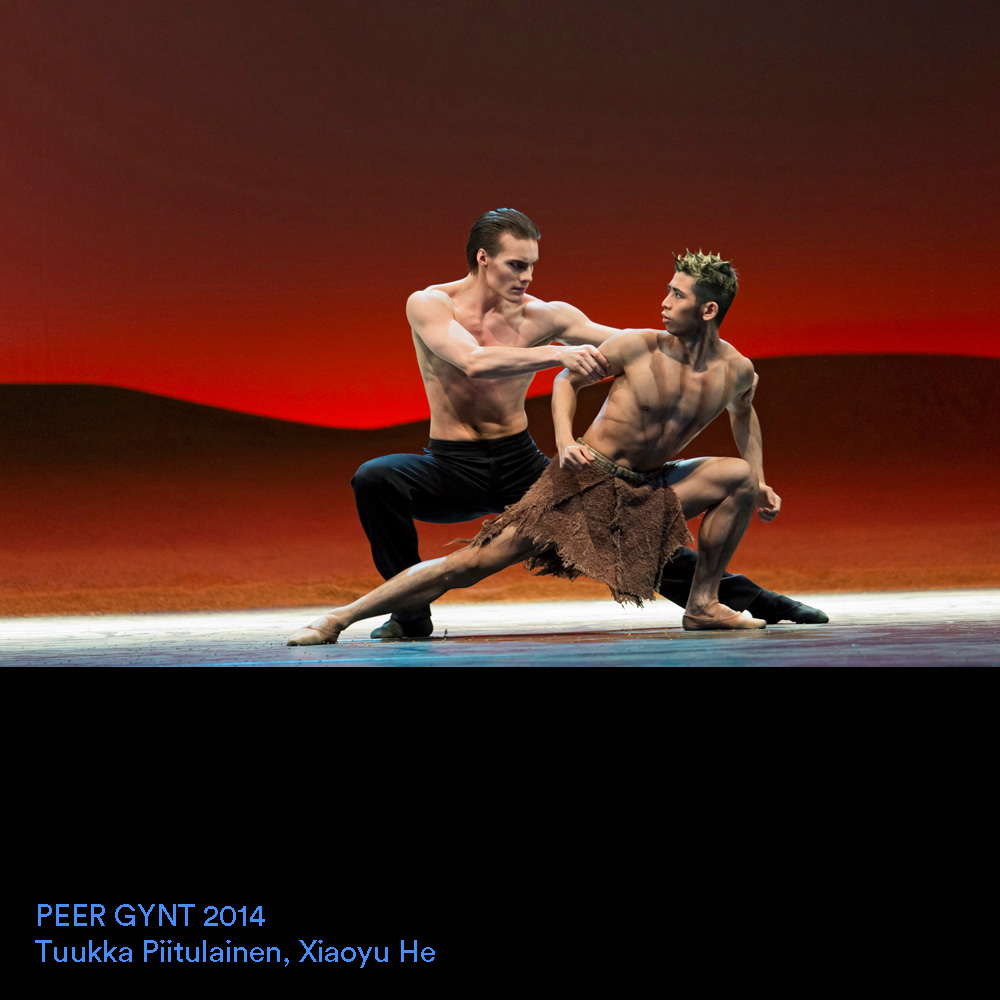

Besides his own works, Greve introduced new story ballets, such as Javier Torres’s Beauty and the Beast and Jorma Elo’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Alice in Wonderland. New interpretations of traditional stories comprised Terence Kohler’s Cinderella – A Tragic Tale and Natália Horečná’s Romeo and Juliet. Guest choreographers included Nicole Fonte, Jacopo Godani, Nacho Duato, Alexander Ekman, and more.

Winds of change

As Kenneth Greve’s tenure was nearing its end in 2018, discussion of harassment spread rapidly across the globe and from the entertainment industry to all cultural fields. Problems in traditional ways of working surfaced in ballet companies around the world, and the dancers of the Finnish National Ballet also came out with their experiences of inappropriate behaviour. Consequently, Greve was relieved of his managerial duties a few months before the end of his contract.

The highly experienced Swedish ballet director Madeleine Onne, who had headed both the Royal Swedish Ballet and the Hong Kong Ballet, took over as the new artistic director of the Finnish National Ballet. Unlike her predecessor, Onne didn’t create any choreographies herself but focused on managing the group and planning the repertoire instead. After her appointment, she decided to focus on classical ballet and preferred contemporary choreographers who employed classical technique. The first productions of Onne’s tenure were still Greve’s choices, and just as she was about to get properly started, the coronavirus pandemic put an end to performances. Onne’s tenure has been heavily overshadowed by the disruptions caused by the pandemic, limited audience numbers, and postponed premieres. At the same time, it has been a time of preparation for the centenary of the Finnish National Ballet.

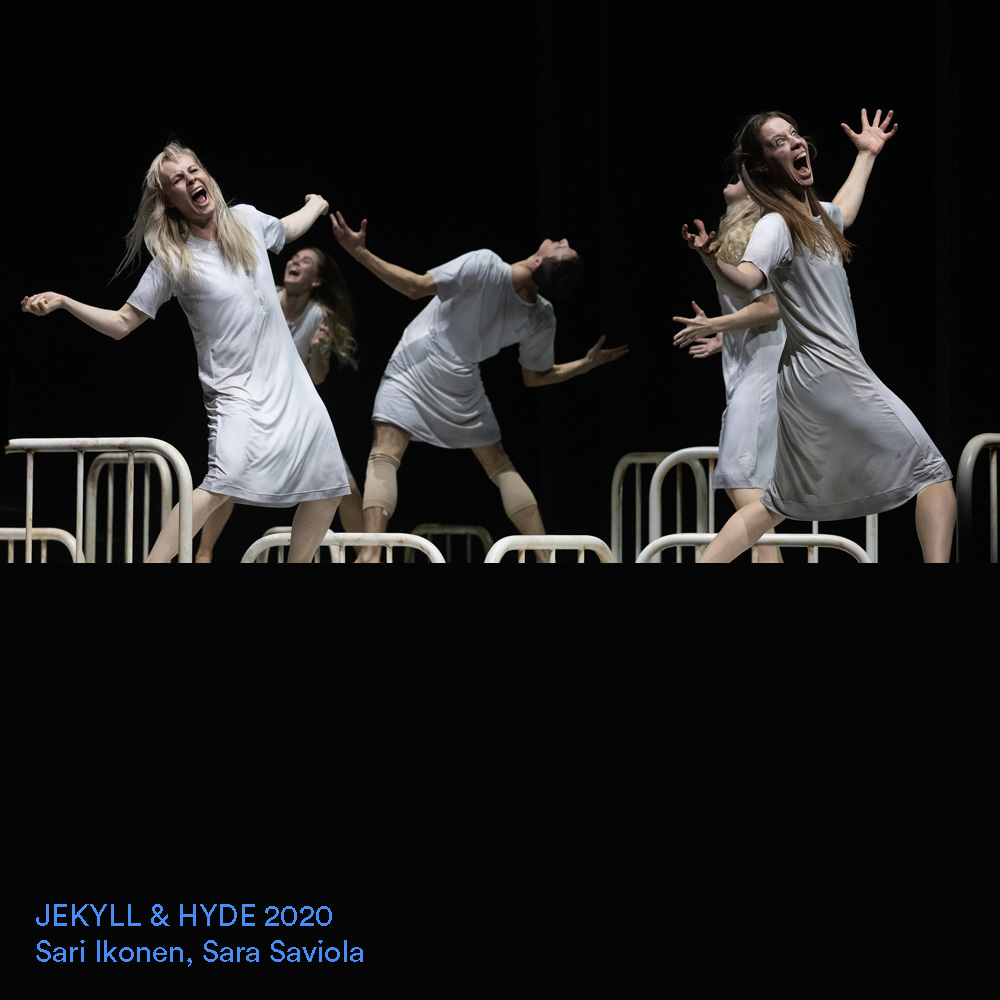

With the centenary in mind, Madeleine Onne commissioned a new version of Swan Lake from David McAllister, in homage to the work that started the story of the ballet company one hundred years ago. She also staged the world premiere of Val Caniparoli’s choreography Jekyll & Hyde with an unconventional horror theme. The centenary repertoire will feature the world premiere of Jorma Elo’s Sibelius. Contemporary dance has been showcased in the Triple Bill evenings of three choreographies, which will continue in the centenary year with world premieres by Finnish choreographers Johanna Nuutinen, Tero Saarinen and Kenneth Kvarnström. Onne also brought a joyful greeting from her home country, Pär Isberg’s Pippi Longstrump, which she had originally commissioned for the Royal Swedish Ballet.

Towards the second century

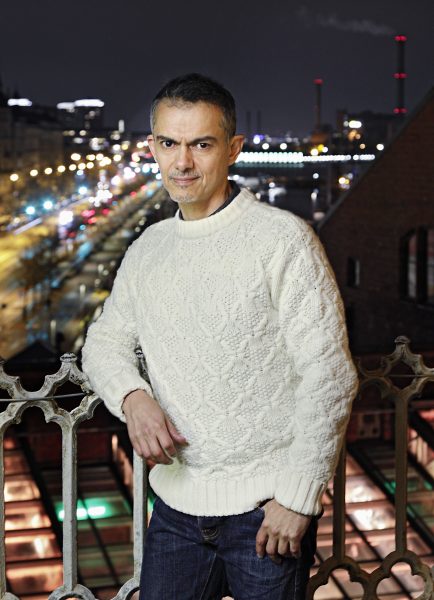

In spring 2021, Madeleine Onne announced that she would not take up the option to extend her director contract. Javier Torres from Mexico, who has built an extensive career at the Finnish National Ballet and the Helsinki City Theatre, was chosen as her successor. He is known as the choreographer of the popular full-length ballets for the Finnish National Ballet, The Sleeping Beauty and Beauty and the Beast. Javier Torres’s contract starts in August 2022.

Text JUSSI ILTANEN

Photos THE ARCHIVES OF THE FINNISH NATIONAL OPERA AND BALLET (Heikki Tuuli, Mirka Kleemola, Stefan Bremer)

Further reading

Laakkonen et. al. (edit.): Se alkoi joutsenesta. Sata vuotta arkea ja unelmia Kansallisbaletissa (Karisto 2021)

75 years of the Finnish National Ballet (The Finnish National Ballet 1997)

Other sources

The archives of the Finnish National Opera and Ballet

Helsingin Sanomat 10.10.2017

Oopperasanomat 2/2001, 2/2008

Pictures of performances and dancers from 2001 to 2021

Watch on Yle Areena

Recommended for you

The Finnish Opera establishes a ballet company

To the new Opera House with Laine and Uotinen

The international National Ballet

Arena tours and school visits

From dancers to choreographers

The Youth Company offers career opportunities

Ballet on television and at the cinema